LOS ANGELES (RNS) — Nine days before Christmas, a group of clergy huddled around a young mother outside the Los Angeles Federal Building, praying for a Christmas miracle that a judge would set bond for her husband at a hearing the following day and release him from immigration detention.

Melanie, 21, who agreed to speak to RNS on the condition that only her first name be used, has been nursing a hope for months that her husband, an immigrant from Nicaragua, would be back home in time to celebrate their infant twins’ first Christmas.

In July, as her husband prepared for an Immigration and Customs Enforcement check-in at the federal building, Melanie was confident he would be spared detention because, she told him, “we’ve been doing things right.” Leaving nothing to chance, she decided the family would go to the check-in together. Surely, she thought, they wouldn’t detain him in front of his wife, a U.S. citizen, and three kids.

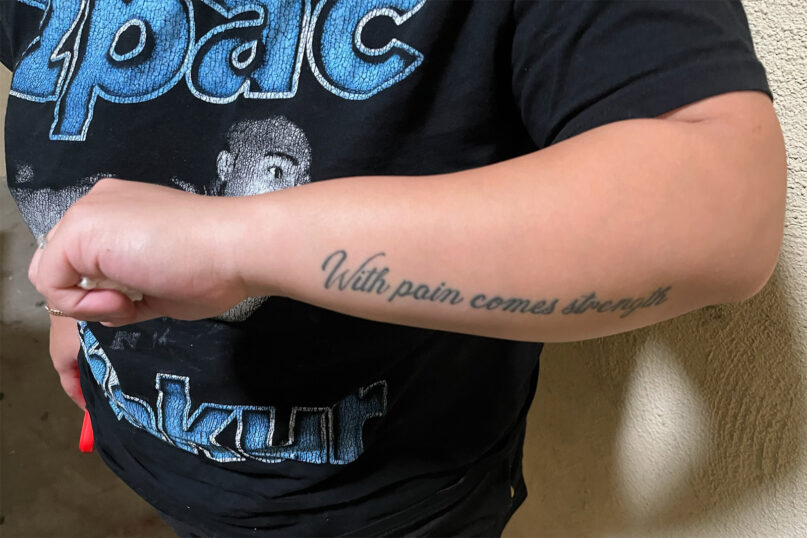

But after her husband had filled out forms and answered agents’ questions about his tattoos, he was taken into a separate room. After 15 minutes, “ all of a sudden, I hear him screaming my name,” Melanie recalled.

Running to him, she saw he had been handcuffed. “ I felt like the whole world just fell on top of me,” she said. With her kids watching, the agents “cornered” her, not letting her approach her husband or say goodbye, but she said, “ I could just tell in his face that he was scared.”

Within five minutes, she was escorted out into the hot July sun. Without their father, there weren’t enough hands to carry the twins’ car seats and her toddler daughter.

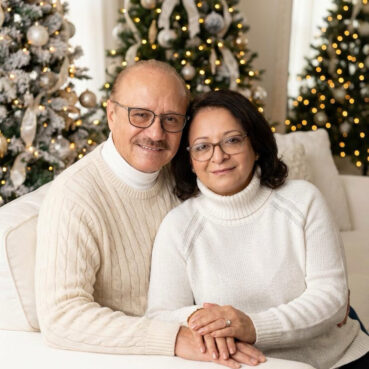

It was there, stranded on the sidewalk, that Melanie met the Revs. Amparo and Carlos Rincón, married Pentecostal pastors who belong to a network of Los Angeles faith leaders who are supporting families broken apart by the Trump administration’s mass deportation policies.

“She looked younger than my daughter,” said Carlos. His wife approached the crying mother, whose eldest was inconsolable after what she had witnessed. The Rincóns have since helped Melanie with diapers, baby formula and groceries, in addition to praying for her and offering to pay her 25-year-old husband’s bond through Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice, colloquially known as CLUE.

Amparo and other women lead an interfaith group with CLUE that meets every Tuesday to march in prayer around the federal building, a center for Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The group calls itself the Godmothers of the Disappeared.

Melanie’s family is just one of many the pastors have found on their weekly visits. Carlos Rincón said his church, which he asked not be named out of fear of retaliation, is supporting about 25 families. One woman, a wife separated from her detained husband, texted RNS in Spanish: “There is no Christmas for separated families.”

Carlos and another group of pastors with his organization Matthew 25, alongside CLUE, plan to break away from their other pastoral responsibilities on Christmas Eve to hold a vigil outside the downtown ICE center, preaching one of his central messages that “ God himself experienced what immigrants experience.”

Even so, he acknowledges, “it is hard.” He said, “ there are too many needs and too many people in so many difficult situations.”

As Advent came and the Rincóns preached about the meaning of Christmas, they faced the emotional devastation of families struggling to cling to hope. It wasn’t until Dec. 1, when Olga, a worship team leader, learned her husband had been detained, that the detentions affected the church directly.

Since then, Olga wakes up too depressed to sing. She’s having trouble eating and sleeping. Despite that, she said in Spanish, “I try to go (to church) because I know God is the one who gives me the strength to continue. He is the one who is with me every day.”

But still, Olga said, “because of what we’re living through, I don’t have a head to think. It doesn’t feel like it’s Christmastime.”

The Rev. Ada Valiente, who supports at least 30 separated families with her husband, Melvin, through their We Care ministry, said that several mothers are suffering a mental health crisis. Struggling to make practical plans to address their immediate needs and unable to plan for their future, they have little time to think about celebrating Christmas.

The Valientes, who lead two American Baptist Churches USA congregations in Los Angeles County, hear about families in need of support from other pastors, other immigrants in the detention centers or sometimes the families themselves.

While the couple will offer advice and recommend reliable immigration attorneys to anyone who reaches out, they prioritize the people with the highest needs — detainees with no family, or whose family cannot visit them because they lack legal status themselves or lack resources. Holistic support provided may include prayer, financial assistance or visits to detained and separated family members.

Melanie and an immigrant mother under the Valientes’ care who requested anonymity because she lacks legal status both said they had been charged thousands of dollars by immigration attorneys who made no effort to help the detained men.

In the months since Melanie’s husband was detained, she has managed to finish his active construction contracts. She had to give up their first apartment and move back in with her mother, who helps with the kids. Melanie also followed the legal details of her husband’s case until she found a new attorney, who was willing to sleep in the detention center’s lobby in order to see her husband.

Melanie met her husband in 2022, when her Nicaraguan mother threw a birthday party for the newly arrived fellow Nicaraguan, who had crossed into the United States legally via the U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s CBP One app. He was granted parole while seeking political asylum.

She said her husband is requesting asylum based on his claim that he was wrongly incarcerated in Nicaragua for two years before being pardoned. “He was just at the wrong place at the wrong time,” she said. He’d already applied to be a permanent U.S. resident before he was detained in LA.

Several of the other women receiving help from the Rincóns and Valientes also fled the human rights crisis of Nicaragua, where co-Presidents Daniel Ortega and his wife, Rosario Murillo, have decimated civil society, including religious institutions, and instituted authoritarian rule. One woman told RNS her detained husband had been arrested, beaten and threatened with worse after participating in a march. They fled Nicaragua, leaving their children behind with relatives. When her husband was detained in the U.S., he was still in need of medical care for injuries from his beating.

Another woman told RNS that she and her now-detained partner refused to join the Ortegas’ socialist Sandinista Party because of their Christian faith, despite threats of physical harm to them and their son. Unless they joined, they were told, they would not be protected by the police. Twice, her husband was detained without cause in Nicaragua, she said.

Both women asked for anonymity because they fear deportation.

Ada Valiente, whose brother was a political prisoner of Nicaragua’s conservative Somoza dictatorship, fled with her family to the U.S. when she was a child, arriving without legal documentation but later becoming a citizen. A bivocational social worker before she retired to work full time in ministry, she has long assisted migrants from Nicaragua and political asylum-seekers.

Valiente’s faith calls her “ to help the most vulnerable and those that don’t have a voice,” she said. Every other Thursday, her women’s group members go to the detention center, where they sometimes are a detained immigrant’s first visitors in six months. “We all cry with them,” she said.

While many detained immigrants find strength in each other or in Bible study, many of those she visits are on psychotropic medications because of depression, anxiety or an inability to sleep, said Valiente. They’ll have limited access to Christmas services because there is only one chaplain for three detention centers, and while pastors like the Valientes can visit, they cannot hold services.

In the weeks before Christmas, even as the Valientes’ congregations prepare for the holiday, Ada Valiente is trying to talk one detained and demoralized man out of signing his deportation papers, while meeting with his wife to make a plan. For a mother who has received an eviction notice since her husband has been detained, Valiente is trying to secure rental assistance. (The woman, Valiente said, may receive a deportation order herself any minute.)

Telling her congregation about the work a few weeks ago, Valiente couldn’t hold back tears. “As normal as it is, you get a little bit with the blues at Christmas,” she said.

Olga said her 10-year-old son, Kevin, a U.S. citizen, told her, “I don’t want to spend Christmas or New Year’s without my dad,” and she has had to tell him, “It’s not in my hands.” Kevin also worries about his mom. When she was late coming home one night, he was sobbing, thinking she too had been detained, Olga said.

One Nicaraguan woman who asked to remain anonymous said she struggles to afford the per-minute charges to talk with her husband on a detention phone. They limit themselves to brief exchanges a couple of times a day, when he asks whether she’s taken her medication or whether she’s eaten her lunch.

When she spoke with RNS in October, she was sleeping in their twin bed holding his pajamas and spending her days beside the giant teddy bear he bought her. In the months since then, she’s had to leave the apartment, sell many of their things and find a job.

On the night Melanie’s husband was detained, one of the twins spent the night with a fever because, she said, he had spent too much time on the sidewalk in the sun when his mother was stranded. She and another mother requesting anonymity said their small children had lost weight since their fathers were detained.

Melanie’s toddler also struggled to sleep, she said: “ The day they detained him, all they gave me was a little plastic bag with his necklace and his watch, so she would just carry it around the house and be like, ‘Papa, Papa.’”

All four women told RNS they lean on their faith, trusting in God to give them strength.

The Nicaraguan mother who fled with her kids said in Spanish that she told her son: “My love, if you want to be with your dad, we have to kneel down every day, because only God can help us. God can touch the heart of the president so that he stops doing these things.”

She added: “We pray for the president, we pray for the immigration officials to understand that what they’re doing is not right because they’re hurting our family.”

Just a week before Christmas Eve, or “Nochebuena” for Latino Christians, Olga’s Guatemalan husband folded to the pressure to sign his own deportation papers, despite Carlos Rincón’s warnings.

“He was putting on a lot of stress and he was threatened, saying that if you don’t sign, we will deport you anyway, and we’re gonna make it harder for you, or if you don’t sign, you will stay for years here, detained,” said the pastor.

And the same day, Melanie’s husband’s bond was denied, with no hearing in sight until April.

“That’s my job, I guess — right now, trying to be with people that are receiving very bad news,” Rincón said.