SPOILER ALERT: The following cultural commentary contains plot spoilers for the movie “Marty Supreme,” now playing in theaters.

(RNS) — If certain films are paradigmatic of an era or a political administration, then “Marty Supreme” will reign supreme as the definitive cinematic rendering of the Age of Donald Trump.

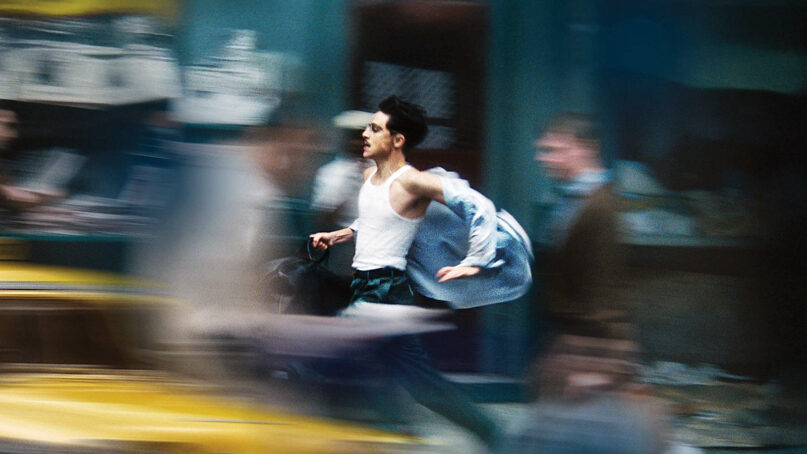

There are some things to admire about the film. The performances are first-rate, including an energetic Timothée Chalamet in the lead role as Marty Mauser, the hard-knocks 1950s table tennis player who overcomes one obstacle after another to become an international star. Gwyneth Paltrow delivers an outstanding performance as an embittered ex-Hollywood icon who unwisely abandoned her career to marry a callously wealthy businessman, Milton Rockwell. Rockwell in turn is splendidly portrayed by Canadian reality TV star and Trump supporter Kevin O’Leary.

The movie is creative, resisting the usual formulas of the underdog sports flick in favor of a frenetic plot that could legitimately have ended in many different ways.

And yet I hated the movie.

I seem to be alone in this. Rotten Tomatoes’ abridgments of several dozen professional film critics’ assessments include numerous claims that this is among the best movies of the year, if not the very best one. Variety called it a masterpiece, while The New York Times lauded it as one of the most exciting and pleasurable efforts of 2025. Meanwhile, The Hollywood Reporter admired the “swaggering confidence” of both the filmmaker and the title character.

“Swaggering confidence” is not the phrase I would use to describe Marty Mauser. He is an abusive narcissist, make no mistake. In fact, he bears an uncanny resemblance to our current president, which makes it rather amazing that many of the same publications that regularly call out the appalling behavior of our president are falling all over themselves to idolize “Marty Supreme.”

Marty lies to just about everyone in the film, saying whatever it takes to advance his own cause. He lies to his family about his prospects, lies to reporters about his origins and lies to the aging movie star about a necklace he stole from her. He also lies to her husband to weasel a free plane ticket to the table tennis world championship in Japan (though, in fairness, that character deserves exactly the kind of perfidy that Marty is dishing out).

Paltrow’s character isn’t Marty’s only married lover; more painfully and poignantly, he has impregnated his neighbor Rachel back in New York and then ghosted her. He returns only when he suddenly needs something — a place to hide from the police, who are pursuing him for robbing his uncle. When Marty finds Rachel eight months pregnant, he initially denies the baby could be his, saying it has to be a product of her miserable marriage.

So he’s a serial liar, a serial adulterer and a serial thief. In addition to robbing his uncle and one of his lovers, he also pries cash out of the vest pocket of a dying mobster, which culminates in one of the film’s most preposterous plot lines. Marty is not in the mob, but he’s more than willing to mop up whatever loot is left over after mobsters kill each other. (Incidentally, the mobster’s love for his dog is one of the more interesting aspects of the story. That loyalty is a perfect foil for Marty, who repeatedly leaves the friends and family he allegedly cares about and doesn’t look back until the moment he needs to take something else from them, whether it’s money or shelter or a ride.)

Throughout, Marty is distinguished by his unwavering confidence in himself. He harbors this self-love without doubt or question, and demeans and lies to anyone who tries to hold him accountable for his actions. Among the people he uses without compunction are a borderline developmentally disabled person and his father, an African American friend and the women he charms for sex. All of these people, he feels, are beneath him in some way.

He even tells Rachel that he has a purpose, while she does not. Her life and dreams are meaningless to him. She, like the other characters he uses and emotionally abuses, are merely objects to be exploited or obstacles to be overcome, never the subjects of their own stories.

In one telling scene, Marty demeans a competitor who has survived the Holocaust, shocking the other characters on screen and us in the audience. He justifies this total lack of compassion for Jewish suffering by saying it’s all right when he makes fun of the Holocaust, because he’s Jewish himself.

Despite all this, the film wants viewers to defend Marty and cheer for him as ardently as he cheers for himself. It asks us to excuse him again and again as he exculpates himself (e.g., he didn’t really rob his uncle; he was just taking the wages he was due). It needs us to believe that the way he treats women is acceptable, and that he is what he keeps telling them he is: their savior, or at least their best option compared with the losers they married.

I hated this Trump-like character, whose selfishness knows no apparent limits. And I hated the film for the way it romanticizes malice and repackages Marty’s abusiveness as good.

Our nation hardly needs to normalize white male megalomania even more than it already has, Timothée Chalamet’s dramatic virtuosity notwithstanding. In the years to come, it will be interesting to see what historians make of “Marty Supreme,” an excellent film about a despicable confidence man.

RNS coverage of other films now playing or streaming:

Amanda Seyfried sees ‘The Testament of Ann Lee’ as a search for divine safety

Rian Johnson on miracles, mystery and his own faith story in ‘Wake Up Dead Man’