Faisal IslamEconomics editor

BBC

BBCBudget days used to be symbolised by the chancellor of the exchequer smiling and holding aloft the famous Red Box outside Number 11. Inside is a red book that contains the measures to be read out in the Budget speech.

These days, however, it’s a blue book that’s in the spotlight. Or more precisely, a chunky chart-filled analysis of the Budget, assessing the cost of government policies, published by a team that sits in a far corner of the Ministry of Justice building – one that few people outside this closed world know much about.

Yet it’s also a department that has extraordinary influence over economic policy.

Now a debate is bubbling about whether this small department, known as the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) – and staffed mainly by young intellectuals and civil servants – is in fact too powerful, with claims from some that it is essentially half-running the government economic policy.

And indeed whether its chairman, Richard Hughes, a Harvard-educated former Treasury mandarin, has in fact become as important as the real chancellor.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesLou Haigh, a former Labour Cabinet minister, has called the OBR an “unelected institution dictating the limits of government ambition”. And just last week the Trades Union Congress accused the “unaccountable OBR” of being a “straitjacket on growth”.

So, ahead of Wednesday’s Budget, is the OBR really the tail wagging the Treasury dog – and if so, could this partly be at Labour’s own hand for having changed the department’s role in the first place?

Under Labour: the OBR’s true influence

Back in March, just after the Spring Statement, I asked Richard Hughes for his response to the critique that had been prevalent even then that the OBR is all-powerful.

His answer, tinged with an uncharacteristic air of exasperation, was firm.

“The only powers we have are the ones given to us by Parliament in legislation,” he insisted. “And those are the powers to produce a forecast, to scrutinise the cost of government policies and to assess whether the chancellor is on the course to meet her fiscal rules.

“The chancellor chooses the policies she wants to implement. She chooses the rules she set for herself, and if she wants to change those rules, she can change those rules. If she wants to change the policies, she can change the policies.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOfficially the OBR monitors the UK government’s spending plans and performance, and releases forecasts for the economy and public finances twice a year, (alongside the Budget and Spring Statement), which assess whether the government is likely to meet the rules it has set over tax and spending.

Yet the irony in the timing of the questions around its influence is that they follow the chancellor herself giving the forecaster even more independence and authority.

What’s more, she herself appoints, with the consent of the Treasury Select Committee, the three members of the Budget Responsibility Committee, who lead the OBR.

When Labour entered office in 2024 it passed a new law giving it new powers to initiate forecasts, even when the government does not ask it to. This was prompted by the Conservatives’ mini-Budget of September 2022, which promised big tax cuts but did not say how they would be paid for, and spooked financial markets.

At the time I reported that the then-Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng had brushed away the offer from the OBR of an official forecast, which could either have given some comfort to the markets that the plan had been fully costed, or impeded the Truss administration’s ability to announce those policy changes. The new law ensures this could not happen again.

It also gives the OBR the ability to question government assumptions about spending by departments, which it did not have before, and provides direct access to Treasury data to help them do this.

WPA Pool/Getty Images

WPA Pool/Getty ImagesEmpowering the OBR was, in fact, part of Rachel Reeves’s plan.

The Chancellor believed that giving the forecaster more independence and influence would improve credibility in UK tax and spending policy; the memories of the Truss-Kwarteng mini-Budget may well have been front of mind.

And yet by September of this year, suggestions of the Treasury’s own reported frustrations with the OBR were circulating.

When I asked the chancellor about a statement from the OBR, issued two months earlier, that “promises made are constantly not kept” on tax and spending, Reeves replied: “The OBR have got an important job to do and their job is to produce forecasts on the economy – not to give a running commentary on government policy.”

Office for Budget Responsibility

Office for Budget ResponsibilityYet the message I received from that exchange with Richard Hughes was clear: the OBR’s true power is not at all at the level its critics suggest.

Warnings about a ‘fiscal technocracy’

Even before Labour’s law change, the then-director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, Paul Johnson, argued that we should be “highly cautious” about moving towards what he described as a “more powerful fiscal technocracy”.

“The OBR has brought discipline and transparency to the fiscal policymaking process, but it is possible to have too much of a good thing,” he claimed. “Choices over how much to tax, spend and borrow are not narrow, technical questions.

“They are inescapably political.”

At the end of October, one month before the Budget, the OBR is understood to have lowered its forecast for productivity – a measure of the output of the economy per hour worked – by 0.3 percentage points. Productivity plays a key role in long-term growth prospects and therefore can influence Budget decisions.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies think tank, for every 0.1 percentage point downgrade in the productivity forecast, government borrowing would increase by £7bn in 2029-30 – meaning a 0.3 point cut could add £21bn to Rachel Reeves’s Budget black hole.

This all has knock-on consequences for any chancellor. For example, if this downgrade had been given when, say, Jeremy Hunt was chancellor, he would not have been able to offer pre-election National Insurance cuts that he did in March 2024.

But the bigger issue is how much credit the government should get for “pro-growth measures”, such as planning reform or easier post-Brexit trade terms with Europe. The more this is forecast to help medium-term growth, the smaller the gap in the Budget maths.

SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty ImagesSome on the Labour left have identified the OBR as a core structural reason why a government with a massive majority cannot act decisively on its instincts. A version of that view has spread now to some on the Labour right too.

Praful Nargund, director of the Good Growth Foundation, who unsuccessfully stood against Jeremy Corbyn in last year’s general election, said last week: “The Office for Budget Responsibility was created to enforce austerity. But in its attempt to restore credibility, it has pushed us further down the spending-cut rabbit hole without an end in sight.

“A body designed to police cuts is now being asked to referee a strategy for growth, and it simply isn’t built for the task.”

But Richard Hughes told me in March he was simply accounting for the numbers, and that it is the chancellor and Parliament that have £3 trillion a year worth of power to make decisions on either raising revenues or spending them.

A need for ‘reconstruction’

In late September 2008, as the world and Britain especially was convulsed by its biggest ever financial crisis, the Conservative Party published an obscure pamphlet titled “Reconstruction”.

British building society Bradford & Bingley had just been nationalised; US investment bank Lehman Brothers had collapsed a fortnight before; and half the British banking system was being prepared for state bailouts, and the pamphlet reflected what researchers were saying was best practice in the field of fiscal policy.

It drew little attention, yet it was from this pamphlet that the idea of the OBR was born.

Getty Images

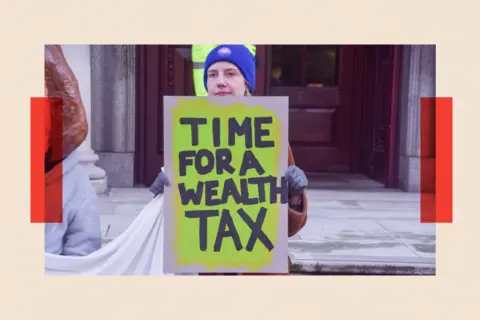

Getty ImagesThe office was first established by the coalition government in 2010, then put on a permanent statutory footing in March 2011.

Yet Chancellor George Osborne predicted that appointing independent economists was going to cause the coalition government some problems.

Take the fallout after Robert Chote, then chair of the OBR, published a chart showing spending levels at their lowest since the 1930s.

It prompted my BBC colleague Norman Smith to describe the “road-to-Wigan-pier” style austerity, (a reference to the George Orwell’s indictment of living conditions in the industrial north of England).

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesSince then, the former Prime Minister Liz Truss, has made claims that a “deep state” played a part in bringing down her brief government – “the economic establishment, who fundamentally don’t want the status quo to change”, as she put it.

As for the OBR, she once said: “Treasury officials go from the Treasury to the Bank of England, to the OBR to the Resolution Foundation. They go to Goldman Sachs, they… it’s the same people.”

During the Johnson-Sunak era, the OBR also published charts that the sitting government would not have welcomed, which showed the tax burden reaching post-World War Two highs.

It is the Labour government that strengthened the OBR – and the distinguished CVs of the three members of the Budget Responsibility Committee ensure that it is taken seriously.

Richard Hughes and Tom Josephs both had senior positions in charge of fiscal policy at the Treasury, while Prof David Miles is a former member of the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee and chief economist at Morgan Stanley.

A tax rise speculation hamster wheel

Insiders have told me there will be important changes to how the dynamic between the OBR and the Treasury will function in future.

In essence, the OBR’s judgement of the amount of room for manoeuvre – the so-called “headroom” calculation – will now only be made once a year, from this Budget onwards. So, the tense process of the Treasury waiting on every bit of number crunching from the OBR will happen only in the run up to a full Budget.

It is a recognition that the current system has led to an ever-spinning hamster wheel of tax rise speculation.

However, defenders of the OBR say it is not the fault of the forecaster. And the International Monetary Fund (IMF) advises the UK that raising the headroom is the best way to stop the doom loop of tax-rise speculation harming consumer and business sentiment.

The chancellor has all but announced her strategy to increase headroom figures at the Budget. The amount will be closely watched in the markets.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty ImagesUltimately, the mini-Budget of 2022 showed how much the OBR’s role is respected in the markets: this was stressed by the Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey at emergency meetings in Downing Street at the height of that crisis.

Plus, even if the OBR did not exist, the government’s Budget decisions would still be constrained by the reaction of markets.

The UK is, after all, reliant on the “kindness of strangers” – foreign buyers of our debt. As the Chancellor points out now, they are increasingly likely these days to be a foreign hedge fund than a UK pension or insurance company.

So, those who now want to diminish the role of the OBR, will have to demonstrate alternative and convincing means of proving their own credibility, both on the numbers and on their political authority to drive through policies.

And yet other countries do manage without institutions such as this. So, for now, there is a serious debate emerging at this Budget, not just about the Chancellor’s policies. The role, record, and future of the OBR is definitively in play.

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.