(RNS) — The doors to St. Andrew’s Church in Ann Arbor, Michigan, which open at 7:30 a.m. on weekdays, opened to a crowd that had been gathering since 6 a.m. in the autumn chill. They were there for a hot breakfast. I was at the church with my daughter, Anna, a fourth-year medical student, one of a team of three volunteers with Wolverine Street Medicine, a favorite extracurricular activity of University of Michigan medical students. Today they were providing foot care in a makeshift clinic they had set up behind a screen in the church’s vestibule.

We had to unpack the trunk of Anna’s car. First was the collapsible green cart that we unfolded and stocked with gauze, Band-Aids, anti-fungal lotions and then the instruments she picked up from the autoclave at the medical school.

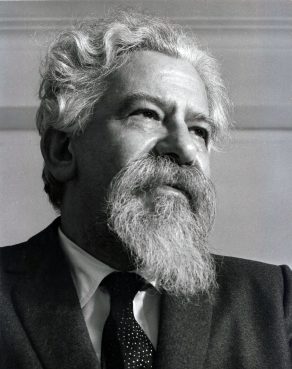

Watching her organize these supplies was among the many moments of “radical amazement” happening that morning, a term first coined by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. “Radical amazement has a wider scope than any other act of man,” Heschel wrote in his 1955 book, “God in Search of Man.” “While any act of perception or cognition has as its object a selected segment of reality, radical amazement refers to all of reality.”

Heschel, who died in 1972 at the age of 65, was a theologian, writer and social justice activist. He appeared with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., most notably crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 alongside King and a young John Lewis.

As I watched Anna work, I thought back to the baby I once rocked to sleep, drowsy after nursing, with the same sense of awe and wonder, and yes, radical amazement, I’d had back then. Anna treated each of her patients with care, appreciating that they are made in the image of God. As a physician-in-training, Anna has already seen things I never have. She will be privy to life histories I will never hear firsthand in my bubble of a world.

On that morning, my daughter knelt on the floor to do her work patiently and unassumingly. Foot washing was part of the hospitality the biblical Abraham offered to strangers in the desert, and Jesus washed the feet of his disciples. In modern times, washing the feet of the poor was crucial to Pope Francis’ ministry.

My daughter shied away from comparisons, saying, “This is why I went to medical school. To help people.” These young doctors epitomized Heschel’s view that “(t)o perform deeds of holiness is to absorb the holiness of deeds.”

In his 2024 book “Rough Sleepers,” Tracy Kidder profiles Jim O’Connell, founder of the Boston Healthcare for the Homeless Program. O’Connell, a Harvard-trained physician who worked for a year at the Pine Street Inn after an internship with Mass General Hospital, devoted his career to providing medical care to homeless patients. On O’Connell’s very first day at Pine Street, the nurses in charge told him he would begin his training by soaking feet for a month. O’Connell had to refrain and retrain himself from offering diagnoses and just listen.

“Feet were diagnostics in themselves,” Kidder writes, how “(t)hey revealed important internal problems. … You could also read a patient’s likely future in the signs that frostbite leaves on the toes.”

Anna asked me to walk around St. Andrew’s dining room and check in with the people eating breakfast, asking each one to sign up for a time slot in the clinic. I took in the crisp white paper tablecloths and the silk flower arrangements on every table and thought of the Jewish commandment of hiddur mitzvah, the obligation to beautify one’s surroundings.

I took down the names of patients who requested their feet be checked for blisters, diabetic ulcers, fungus or simply to have their toenails clipped. I couldn’t shake the feeling that many were simply skin hungry for human touch.

Over the whir and buzz of conversation and care, some patients told my daughter and her fellow medical students about their lives as rough sleepers, sleeping in the open air, in cars, doorways or abandoned buildings. According to the National Alliance to End Homelessness, more than 700,000 people were homeless in the United States as of January 2024. Approximately 60% stayed in shelters, while the rest lived on the street or in cars.

Almost everyone who comes to the clinic at St. Andrew’s is on their feet all day and night. My daughter peeled off their damp socks and went to work.

A patient I’ll call J told Anna his feet were scary; Anna told him nothing is too scary. R, a person with diabetes, told Anna that she, R, was God’s messenger on earth. Anna nodded. She didn’t miss a beat, she didn’t judge.

She applied fungal cream to H’s foot in the hope of clearing his infection. C was at the end of the list, waiting patiently. She said she’d just been offered an apartment. She told me about her grandchildren, one of whom was on his school’s honor roll. “Maybe he’ll be a doctor like your girl,” she smiled.

Heschel wrote, “A Jew is asked to take a leap of action rather than a leap of thought. He is asked to do more than he understands in order to understand more than he does.”

The morning I spent with Anna in the foot clinic, I took a page from Rabbi Heschel and witnessed Anna’s good deeds transform into its own prayer. I watched as she sent each of her patients on their way with a couple of pairs of clean, dry socks and the promise that she’d be there on their next visit.

It was another moment of radical amazement, as she tended to soles and souls.

(Judy Bolton-Fasman is the author of “Asylum: A Memoir of Family Secrets.” A version of this article first appeared on Cognoscenti, an essay and opinion section of WBUR’s website. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)