(RNS) — How does one remain whole in captivity under torture and starvation conditions?

Gratitude goes a long way.

It sounds crazy to think a person could find anything to be grateful for when held hostage in a tunnel in Gaza for almost 500 days, but in his new memoir, Eli Sharabi, who was kidnapped from Kibbutz Be’eri, near the Gaza border, on Oct. 7, 2023, tells how he survived and helped those with him function as best they could under excruciating conditions and near starvation.

Sharabi had some abilities that assisted him. Having grown up in a family from Morocco and Yemen, he spoke fluent Arabic, allowing him to communicate with his captors and understand what they said to and about him and his fellow hostages. He was older than some of those who were held with him, too, and as a manager on the kibbutz, as a parent and spouse, had more experience with thinking outside himself.

Some of his capabilities were a result of religion, which gave him and some of the other hostages a structure that helped them survive. Sharabi writes of his first days in captivity with a Thai worker on a neighboring kibbutz named Khun, “I understand I have a role with Khun, and I embrace it: to mediate the situation for him, to give him strength. … On hard days and long nights, I try, with broken words in two languages and pantomime gestures, to spark hope in him, to remind him that this is temporary, that it will pass.”

This caring for another extends to three younger men, Alon Ohel, Or Levy and Eliya Cohen, whom he tried to encourage and strengthen. The relationship, which he believes boosted the spirits of the younger men, was mutually beneficial: “I’m always thinking of what to tell him to boost his self-confidence, to make him realize he’s got this. What to tell him to make him realize that he’s giving me strength too. That his concern for me, his care, and even the way he treats me as a father figure gives me more strength than I had before.”

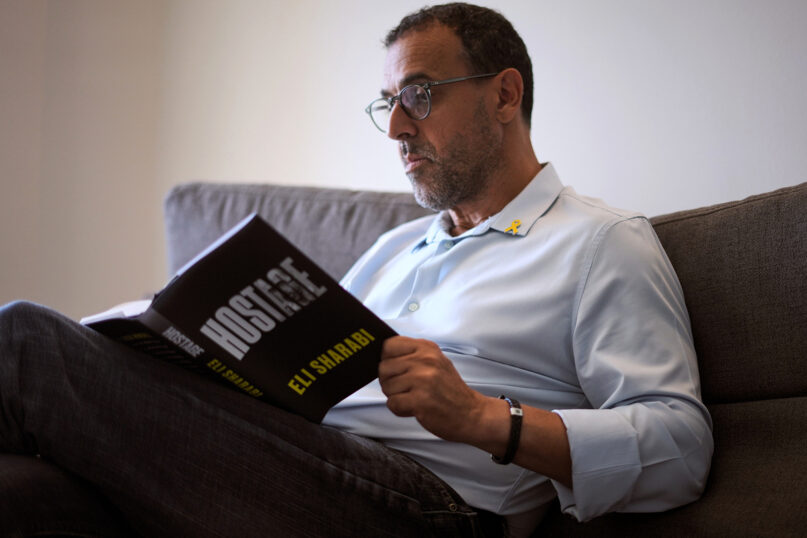

Eli Sharabi, who was abducted during the cross-border attack on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, and held hostage by Hamas for 16 months, poses with his new book, “Hostage,” for a photo in Herzliya, Israel, Sept. 18, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariel Schalit)

Despite their captors’ cruelty, the men learned that, even with differences of opinion and personality and with no small number of fights, they could care for each other and thereby improve their collective condition.

At one point the four argue about what to do when the captors offer food to one hostage but not the others. At night if they needed to use the bathroom, they had to pass through the room where the captors ate. The taunts from Hamas guards were continuous – “We will give you a slice of fruit, a piece of halvah if you recite a Quranic verse, if you say you believe in the prophet Muhammed.”

Some of the hostages felt that because each of them was starving and their own lives were important, they should each make the decision that was best for their own survival and eat when they could. One day, Ohel refuses the piece of fruit, telling his captors, “If it’s not for everyone, then I’ll pass, thank you very much.” The captor says “Bravo” and the other three realize they have defied the captors’ logic. Sharabi writes, “From that moment on, we follow his lead, despite the hunger and the temptation. Whenever they offer us something to eat separately, we turn it down.”

The seven hostages in Sharabi’s group listened at one point to an ultra-Orthodox Jewish captive recite the grace after meals. The words “unfamiliar to most of us, dissipate through the sealed tunnel, dozens of feet beneath Gaza, and enter our hearts,” Sharabi writes. “I close my eyes. The words swirl around me: You open Your hand and satisfy the desire of every living thing… Who provides food for all…Who gave our ancestors a precious, good and spacious land… Have mercy O Lord our God.”

Gratitude takes nonritual forms as well. Sharabi decides that before they go to sleep at night, his three fellows would “try to think of something good that happened to us that day. Whatever day we just had. I came up with it spontaneously one evening, to lift everyone’s spirits. I told them, ‘Come on, let’s think of something good that happened today, just one thing,’” he writes. “One good thing might be, for example, if they suddenly let us drink tea. Or if the tea was sweet. Another good thing might be if a particularly cruel guard we dislike doesn’t show up that day.” Slowly, the gratitude works itself into other parts of the day. “We find ourselves searching for the good things for which we can express gratitude in the evening,” Sharabi writes.

Sharabi understands that, just as those above their head in the streets are fighting, he and those captive with him must also fight. They need not just to survive, but to hope, to have optimism that their situation is only temporary and will improve. “Hope is never something that comes easily. It’s always something you’ve got to fight for, to work on. Like Kiddush every Friday night, like Elia’s Havdalah songs at the end of every Sabbath, like the prayers that open every morning, this circle of thanksgiving is something that we stick to, cling to cleave to. To search for something good. To stay optimistic. To win.”

A Red Cross vehicle carrying Israeli hostages drives by at the Gaza Strip crossing into Egypt in Rafah on Nov. 25, 2023. (AP Photo/Fatima Shbair)

Sharabi considers that he won by staying alive. When he was freed after 491 days of captivity “and suffering and darkness and pain,” he found that, though he was safe, his wife and two daughters had been murdered, as well as his brother Yossi, who had come to the kibbutz because Eli was there. Somehow, he has to continue his life with the family he has – his mother, surviving brother and two sisters, along with their families.

His life will never be what it was on Oct. 6, 2023, he realizes, and as accounts of other hostages show. But he remembers something the late Hersh Goldberg-Polin, who was killed in captivity in August 2024, had taught him and the others. “He who has a why can bear any how.” It is a quote from psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl’s 1946 book later titled “Man’s Search for Meaning.” Sharabi’s why is the subject of the book.

I had this book sitting on my desk until the recent ceasefire deal was negotiated, afraid to expose myself to the fearsomeness of the torture the hostages underwent. I don’t feel it is my responsibility to absorb all the details of atrocities perpetuated in part to instill fear in a larger population.

The book’s stark cover, black and white with the word “Hostage” and photo of Sharabi, contributed to my hesitation. Once I could afford some optimism about the release of the 20 living hostages, I opened it and was glad to read the propulsive narrative, written simply but with powerful messages.

The survival of any human in the brutal physical and psychological conditions they were held in is remarkable; that Sharabi not only survived but encouraged others and enabled all four of them to survive — and created a framework for both ritual and spontaneous gratitude — is a remarkable act of human flourishing.

(Beth Kissileff is co-editor of “Bound in the Bond of Life: Pittsburgh Writers Reflect on the Tree of Life Tragedy.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of RNS.)