(RNS) — With a global pandemic raging, political upheaval in her partner’s home of Myanmar and dramatic polarization at home in the U.S., Erin Kamler, an American musical theater composer and scholar who lives in Thailand, found herself in search of refuge.

She found it in the Pali, Sanskrit and Hebrew mantras of Buddhism and Judaism. Humanity has “always had to deal with how to move through loss and grief and upheaval and change,” Kamler said. “These prayers and chants are reminders that we have the tools we need to overcome these struggles.”

Those tools are both “timeless and timely,” she said: collective empathy, love and resilience.

No stranger to these ethics, Kamler has used feminism as a “spiritual framework” in her wide-ranging academic research on gender equality, working with nongovernmental organizations and civil society groups across Southeast Asia. Her award-winning musical projects, including “Divorce! The Musical” and “Land of Smiles,” combine her expertise in music composition and international diplomacy to shed light on women’s rights through the arts.

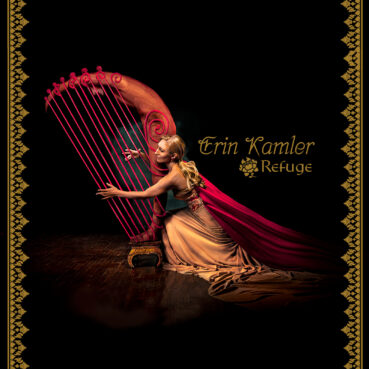

Drawing from her early 2000s journey as “Mantra Girl,” the composer and activist weaves together piano-vocal melodies, devotional chants and cross-cultural styles in her newly released album, “Refuge.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When did devotional music first come into your life?

By surprise. Back in my 20s, when I was living in New York, I discovered Kundalini yoga, and mantras and chanting are really part of that practice. I just became really immersed in it and ended up recording several albums in that genre, which really resonated with people and became a big part of my life.

At that point, I needed a way to ground myself, and wanted a practice that was my own, something I could turn to that wasn’t having anything to do with organized religion, but that was really about providing a sense of peace, and a sense of healing and a sense of comfort. The practice really gave me all of those things. It was very similar to the arts in a lot of ways, a space where people come together, where people are really focused on the liveness of it, the ritual of it. It felt comforting to me.

My real artistic background is in musical theater and as a songwriter, so I went on to do a lot of work in that area, but those meditations stayed with me, and they were something that I carried through everything else that I have done in my career. I always thought, I want to return to this genre, but maybe in a new way, in a way that tracks more with my evolution later on. And so this album was kind of about that return.

How is the album, which speaks to compassion in the face of life’s suffering and grief, both “timeless and timely”?

Erin Kamler’s “Refuge” album cover. (Courtesy image)

During the pandemic, I was living in Thailand and my partner is from Burma. The border was closing there, and so my partner got on a plane and we were basically here (in Thailand) for three years. I couldn’t go back to the States, and a very violent military coup came to Burma. So my partner couldn’t go back. In Thailand we just felt like we were home. We felt so cared for and held by this culture of kindness and sanity and compassion. Yet, I really found myself looking out around at the world, and particularly the U.S., and seeing it just fracture with all the social and political polarization that was going on, which was really heartbreaking, and then in Burma, people were getting killed in the streets, and things were getting worse and worse.

So some of this album — the song “Temple,” for example — is explicitly about the coup in Myanmar, and the mantra “Buddham saranam gacchami” literally means “I take refuge in the teachings of Buddhism.” It’s inspired by activists who went into the temples and dressed as monks to hide from the junta.

Then, in zooming out to right now, polarization is getting really extreme all over the world. We’re seeing many places tip toward authoritarianism, which thrives on fear. It thrives on division and dehumanization. It asks us to really distrust each other and shut down our empathy. I wanted to combat that, and say no to that way of thinking and behaving. There’s a need for a feeling of safety or refuge, of interconnectedness, and a trust that we can have some kind of shared understanding, rather than fracturing.

Can you tell me about your process in finding the right mantras to fit your vision for this album?

At its heart, this album is about shared grief and loss, and it’s counterpart, which is love. The amount of grief we have is really equal to the amount of love we feel. I chose to focus on the Hebrew and the Pali and the Sanskrit mantras that spoke to those processes of working through grief as well as honoring love.

Some of these were prayers or mantras I hear in my everyday life here in Thailand. Some, like the Hebrew prayers, came from my experiences having attended synagogue or celebrating Jewish holidays. I also became more involved with the Chabad community here in Thailand, which is really cool.

How did you manage the different languages of the mantras?

I don’t speak Hebrew, but I consulted with some friends in in the Jewish community who are fluent. For the Pali and the Sanskrit, I consulted with the Nepali musicians I worked with in Kathmandu, who were just sort of immersed in those chants and that language, because I wanted to make sure that I was honoring the mantras and representing them correctly.

Mantras allow people to have a shared experience that’s not necessarily based in narrative storytelling, that’s not necessarily bound to one common language or a common educational or cultural background. They cut across contexts in a very profound way. They’re accessible to everyone, and that allows for a shared musical experience. There’s something really profound in this genre, and I’m really thrilled to be creating music in the genre again.

How has music played a role in your personal spiritual journey?

I wasn’t really raised with any kind of organized religion, but I did grow up immersed in the arts. My dad was a huge lover of music, particularly jazz, and my mother was a visual artist. She grew up in South Dakota and was raised Lutheran, and he grew up on the East Coast, in New Jersey, and was raised Jewish. They weren’t religious, but they were both artists. So in a way, the arts and music kind of became what I would think of as my spiritual foundation. It’s an opportunity for personal reflection, for interconnection with other people, and this kind of sacred interconnection to other people.

What have you learned in creating the album?

I learned more about my Jewish heritage, and I learned about some of the prayers that I had maybe heard or been even reciting growing up, but didn’t really know what they meant. The Barucha is a blessing that honors all of the parts of life, even the difficult moments in life — this idea that there is a blessing for every moment in life. That connected in a lot of ways with Buddhism’s focus on letting go, and honoring even things that we perceive as loss and accepting them.

I felt like this whole thing was a grand experiment, bringing all these different perspectives and emotions together. I didn’t know if people would really relate to it, but I went to Nepal with my recording engineer, and met these wonderful, just brilliant, world-class folk musicians. Not having heard the music, they started playing along as I started playing. It was like this instantaneous connection. I thought, “OK, I’m doing something right.”

Then I recorded all the strings remotely with David Shenton’s orchestrations in New York. And with these American string players, an Irish harpist, an Iranian guitarist, everybody got it. Everybody just embraced it. There was a sense of radical openness to it among all the musicians.

It really reminded me that the arts are this pro-social space, where there isn’t a lot of shutting doors and shutting things down. And I think that’s what we need right now.