Christine RoTechnology Reporter, Hamburg

Quest One

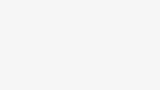

Quest OneIn a spotless, hushed factory near Hamburg in northern Germany, industrial robots stand ready to assemble the components of electrolysers.

These devices split water into oxygen and hydrogen. The ones manufactured by Quest One use proton exchange membranes to accomplish this.

The robotic arms crafting Quest One’s electrolysers are faster and more reliable than the humans they’ve replaced.

But that speed and efficiency is not fully needed yet, as the order volume for electrolysers is far below the facility’s capacity.

The mismatch between supply and demand is evident from Quest One’s own staffing.

This Hamburg plant can support almost double the current staff. But earlier this year, the company had to lay off 20% of its workforce in Germany.

“The market itself is not picking up organically,” acknowledges Nima Pegemanyfar, Quest One’s executive vice president for customer operations. “Demand is the problem. It’s not supply.”

Demand is sluggish in part because green hydrogen – hydrogen produced via electrolysis, using renewable electricity – remains pricey compared to the fossil fuels used to make other types of hydrogen.

Low-emissions hydrogen production makes up less than 1% of hydrogen production globally. This includes both green hydrogen and grey hydrogen, which is produced from natural gas with the resulting carbon dioxide captured and stored.

Scaling up would help bring down the costs of green hydrogen, but many projects remain small-scale.

Quest One is hoping that production of green hydrogen will eventually cost €4 ($4.60; £3.50) per kilogram – about half of the current price in Germany, according to the company.

The gap is not only between supply and demand.

There may also be a disconnect between the sectors where green hydrogen is most badly needed (for instance, for high-temperature uses in the chemical, steel and shipping industries) and the use cases that are less competitive, but still generate chatter.

Christian Stöcker, a communication professor at the Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, is frustrated at the attention paid to hydrogen for heating buildings and powering cars. These would be extremely inefficient, he points out, in comparison to heat pumps and electrification.

Prof Stöcker is also concerned about green hydrogen’s links to fossil fuel companies and automakers. Some critics argue that these companies have an interest in finding uses for, or justifying, fossil fuel infrastructure.

Quest One is part of the Volkswagen Group, which reportedly is considering selling the company it owns (Everllence) that in turn owns Quest One.

Volkswagen would not confirm or deny this to the BBC, or specify whether it had any other plans related to green hydrogen. A spokesperson states, “We are currently reviewing strategic options for Everllence.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMaking prices more competitive will depend on government policy, German green hydrogen companies say. Other than regulation supporting this sector, there’s no plan B.

And then all the infrastructure and investment will stand wasted.

That infrastructure includes a network of hydrogen pipelines planned for northern Germany, snaking out from the Port of Hamburg to a number of hydrogen producers and – it is hoped – industrial clients.

The infrastructure also includes salt caverns to store hydrogen underground, which Storengy Deutschland is building around an existing site for storing natural gas in Lower Saxony.

The company believes that the best way to store excess renewable electricity is to convert it into hydrogen, store it at least 1,000 metres underground, then use it in winter when the need is greatest.

It’s a long and costly process, and regular operations wouldn’t start until the 2030s at the earliest.

Also being planned, for greater supply, are hydrogen transport networks between Germany and places as distant as India, Saudi Arabia, Chile and Namibia.

Hydrogen gas can be converted into ammonia and then transported as a liquid. However, there are efficiency losses, including when extracting the hydrogen on the receiving end.

There are also criticisms of the potential carving up of ecologically or culturally significant locations abroad to feed European industries. This could exacerbate the gap in energy access between the countries supplying and consuming hydrogen.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe German government has stated that hydrogen is necessary for reaching climate targets. But amid high costs it is loosening its ambitions for green hydrogen.

Yet many green hydrogen companies in Germany are calling for more government support to domestic industries and energy stability in competition with China, the world’s powerhouse of green hydrogen production.

Chinese companies account for almost 60% of the world’s capacity to manufacture electrolysers.

Overall, Ivana Jemelkova, CEO of the industry group Hydrogen Council, admits that demand for green hydrogen is not in line with the very high expectations of five years ago.

In the last 18 months, 52 low-carbon and renewable hydrogen projects were cancelled, she says. “That’s a lot of bad news.”

The project cancellations, delays and bankruptcies continue to mount.

For instance, in May 2025, the Norwegian renewable energy company Statkraft decided to stop developing new green hydrogen projects, due to market uncertainty. A spokesperson says that the company will focus on fewer technologies going forward.

But “while some of the individual trees may be falling…the forest, as such, is really growing,” Ms Jemelkova believes. “It’s not hype anymore. But it’s not doom and gloom.”

For the German companies standing ready to produce, store and move green hydrogen, it’s now crunch time. They can’t wait any longer for a supportive market, some say.