(RNS) — Religious leaders are among those objecting to the National Park Service’s removal of a historic exhibit about slavery located steps away from Philadelphia’s Liberty Bell and that featured African Methodist Episcopal Church founder Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, the first Black priest in the Episcopal Church.

On Thursday (Jan. 22), exhibit supporters and city officials learned that NPS staffers had removed panels from “The President’s House: Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation,” an exhibit that, according to a page on the park service’s website, examined “the paradox between slavery and freedom in the founding of the nation.” As of Wednesday afternoon, the website said “Page not found” where that information previously had been.

The open-air exhibit, which opened in 2010, is located on the site where Presidents George Washington and John Adams lived in the 1790s and features a replica of the exterior of the dwelling and a wall with the names of the nine enslaved Africans Washington brought there.

Independence National Historical Park, which hosted the exhibit, was cited in a March 2025 executive order signed by President Donald Trump. Titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” the order directed the U.S. Department of the Interior to ensure that monuments at national sites “do not contain descriptions, depictions, or other content that inappropriately disparage Americans past or living (including persons living in colonial times), and instead focus on the greatness of the achievements and progress of the American people.”

The Rev. Mark Tyler, historiographer for the AME Church and former pastor of Mother Bethel AME Church, which was founded by Allen and is within walking distance of the exhibit, said the loss of the panels is “a gut punch.”

“The feeling around the African Methodist Episcopal Church about the removal of all things related to slavery at the President’s House has been immediate,” he said.

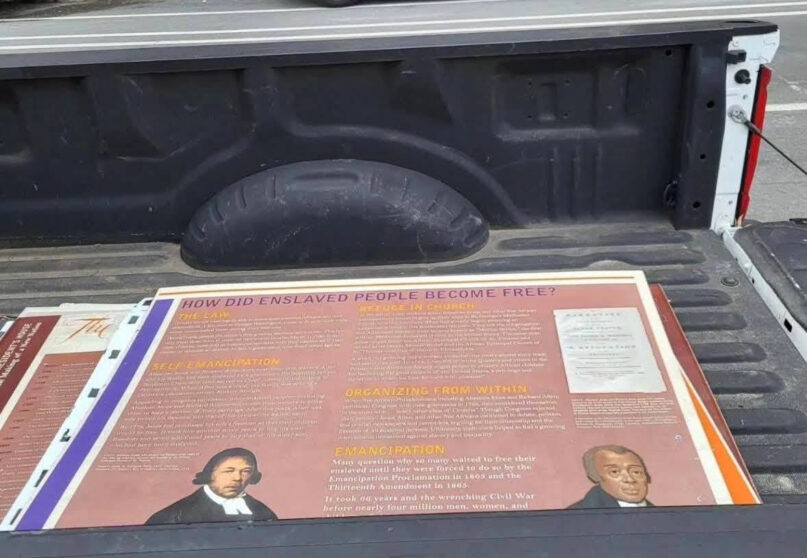

One of the removed panels featured images of Allen and Jones and noted that the two men, born as enslaved persons, were instrumental in starting their churches.

“In the fall of 1792, Richard Allen, Absalom Jones, and other free African members were forced to give up their seats in St. George’s Methodist Church to white members,” the panel read. “They had already begun planning an independent church; this accelerated the plan. They left the congregation and Allen soon founded what became known as ‘Mother Bethel,’ the first African Methodist Episcopal church in the United States. The same year, Jones helped found the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas and served as its pastor. Mother Bethel and the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas continue to thrive in Philadelphia.”

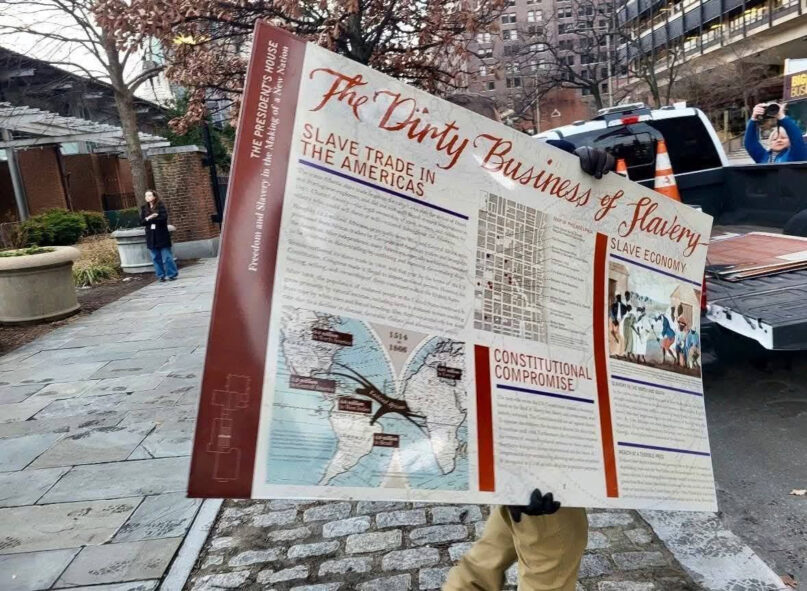

A worker removes a slavery exhibit panel from the President’s House, Jan. 22, 2026, in Philadelphia.(Photo by Mijuel Johnson)

RELATED: Methodist racial history recalled on 250th anniversary of Asbury’s US arrival

In a complaint filed Thursday, the City of Philadelphia sought to restore the full exhibit. Its lawyers said the Interior Department, which oversees the park service, exceeded its authority and the action “reflects final decisions — in accord with presidential directives — to unilaterally rewrite history to suit the current Administration’s preferred narrative.”

The Interior Department confirmed that the March executive order was the catalyst for the removal but did not directly respond to a question from Religion News Service about the safety, preservation and security of the items removed.

“All federal agencies are to review interpretive materials to ensure accuracy, honesty, and alignment with shared national values,” said a department spokesperson in a statement. “Following completion of the required review, the National Park Service is now taking appropriate action in accordance with the Order. We encourage the City of Philadelphia to focus on getting their jobless rates down and ending their reckless cashless bail policy instead of filing frivolous lawsuits in the hopes of demeaning our brave Founding Fathers who set the brilliant road map for the greatest country in the world – the United States of America.”

Roz McPherson, the manager for The President’s House project, which was advocated for by grassroots organizations, said a cross-cultural, intergenerational and ethnically diverse group had been strategizing about protecting the slavery panels after Trump’s executive order. But she said they were “blindsided” by the removal.

Roz McPherson. (Photo courtesy of McPherson)

“We thought we would have some notice, and they took away those panels and didn’t even share with us where the panels were going,” she said.

She said the stories of Allen and Jones had not been widely known. “They were part of a buried history,” said McPherson, a founder of Dare to Imagine Church, an Philadelphia interdenominational and predominantly Black congregation affiliated with the American Baptist Churches USA.

“We totally believe that their interactions and engagement, especially when you’re talking about free and enslaved people in historic Philadelphia, they are a critical part of this history, and faith is a critical part of this history, very much so, and has continued to be throughout the centuries,” she said.

An exhibit panel featuring Richard Allen and Absalom Jones sits in the back of a truck after being removed from the President’s House, Jan. 22, 2026, in Philadelphia. (Photo by Mijuel Johnson)

RELATED: AME Church continues 200-year journey toward racial justice

Arthur Sudler, director of the Historical Society & Archives of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia, where Jones was first a lay reader and later a preacher, said the panels about slavery were a fitting part of the exhibits in Independence National Historical Park, including the Liberty Bell.

“You have this juxtaposition of the bell, which connotes freedom and independence, with the house where there were enslaved people. So, you had this correlation between slavery and freedom, which of course has always run through Philadelphia since its inception because we know even William Penn had enslaved people up through the Civil War,” he said, referring to the state’s founder.