Hundreds of millions of votes cast, more than six weeks of polling, and billions of dollars spent: india on Tuesday will declare a new leader after a mammoth nationwide election that has become a referendum on the last decade of leadership by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

His powerful right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) had set out to win a supermajority in the lower house of parliament – or Lok Sabha – a goal which, if successful, would give it an unstoppable mandate to further enshrine its Hindu-nationalist agenda, deepening India’s Move Away From Its Secular Foundations.

But as preliminary results began rolling in throughout Tuesday, that ambitious goal appeared to be at risk, with the main opposition Indian National Congress performing better than some analysts expected — despite the BJP still in a comfortable lead.

Given India’s strategic position in Asia and its booming economy, the election result will reverberate far beyond its borders, Capturing the attention of the United States, China and Russia in particular.

Some 642 million people cast their vote in the world’s largest election, as swathes of the country was blanketed in searing heat, making people sick and killing dozens.Hoping to unseat India’s charismatic but divisive leader is an alliance of more than two dozen parties, led by the Congress party, which is running on a platform of reducing inequality and upholding democratic institutions which it argues are at risk.

Since assuming power in 2014, Modi has attained levels of popularity not seen in decades, owing to a raft of development and welfare programs, mixed with a strident brand of Hindu nationalism in a country where about 80% of the population are followers of the polytheistic faith.

Under Modi’s leadership, the country of 1.4 billion people has become the world’s fastest-growing major economy and a modern global power, making strides in technology and space. Yet, despite these successes, poverty and youth unemployment persist – particularly in rural areas – and the wealth gap has widened.

Critics also say a decade of Modi’s governance has led to growing religious polarization, with Islamophobia marginalize much of the country’s more than 200 million Muslims, and religious violence flaring up in a nation with a long history of communal tensions.

Graphic: Rosa de Acosta,

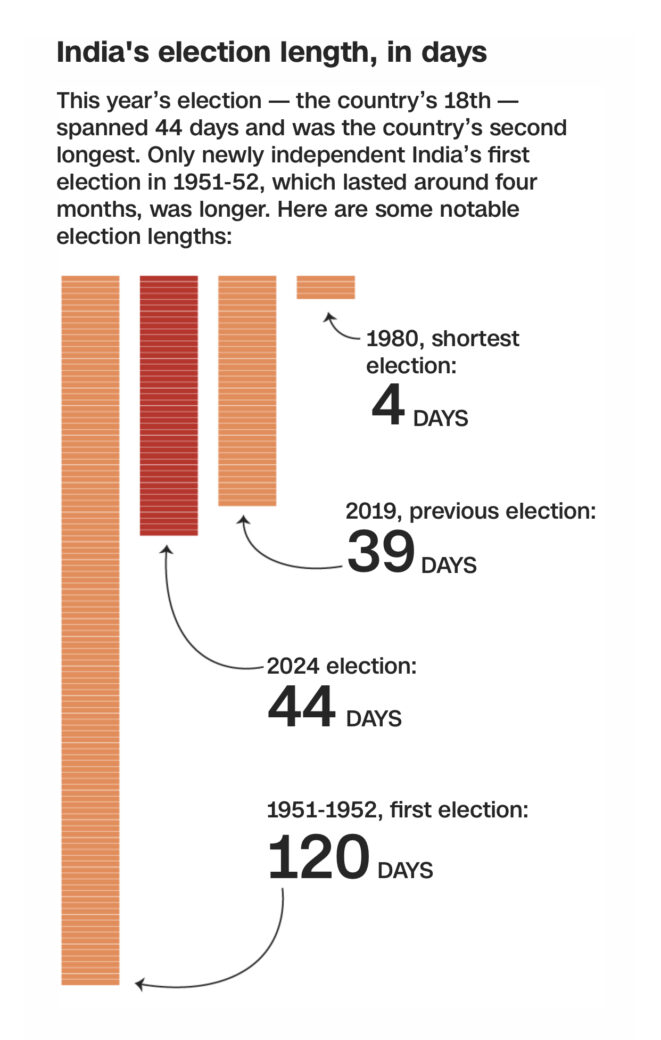

Polling began on April 19 and ended on June 1. Nearly 1 billion Indians were eligible to vote for 543 seats in the lower house of parliament. The leader of the party that wins a majority will become prime minister and form a ruling government.

Modi has set an ambitious target of securing a 400-seat supermajority, with 370 directly controlled by his BJP – up from 303 in 2019 – and the others from its National Democratic Alliance.

His BJP centered its manifesto on job creation and anti-poverty programs, with a focus on women, the poor and farmers. He’s promised to turn India into a developed nation by 2047 and transform the country into a global manufacturing hub. Yet, on the campaign trail, he has been accused of deploying openly divisive rhetoric that has been condemned as Islamophobic, while casting himself as an instrument chosen by God.

Modi sparked a row over hate speech when he accused Muslims – who have been part of India for centuries – of being “infiltrators,” and echoing a false conspiracy voiced by some Hindu nationalists that Muslims are displacing the country’s Hindu population by deliberately having large families. His BJP released several political videos targeting Muslims, one of which is under investigation by police.

Congress has governed India for much of its independent history, having been instrumental in ending nearly 200 years of British colonial rule. But over the last decade, it has struggled to find relevance – partly due to a series of corruption scandals and infighting – unable to break through Modi’s popularity.

Rahul Gandhi, the son of the famed Gandhi dynasty, is the face of the party but lost the past two elections to Modi. He is contending once again from the southern state of Kerala and the crucial state of Uttar Pradesh in the north, also India’s most populous.

Opposition leaders and parties have faced a slew of legal and financial challenges in the run-up to this year’s election, with many accusing the BJP of using state agencies to stifle opponents.

The arrest in March of the popular Aam Aadmi Party leader, chief minister of Delhi and staunch Modi critic Arvind Kejriwal sparked protests in the capital and prompted claims of a political “conspiracy” by his party – claims the BJP has denied.

Kejriwal’s release on interim bail last month galvanized the opposition to put up a tough fight against the BJP, uniting a group of political leaders who were once divided over ideological differences.

The Congress’ manifesto has also been dubbed one of India’s most progressive, pledging “freedom from fear” and vowing to protect freedom of speech, expression and religious belief espoused in the constitution.

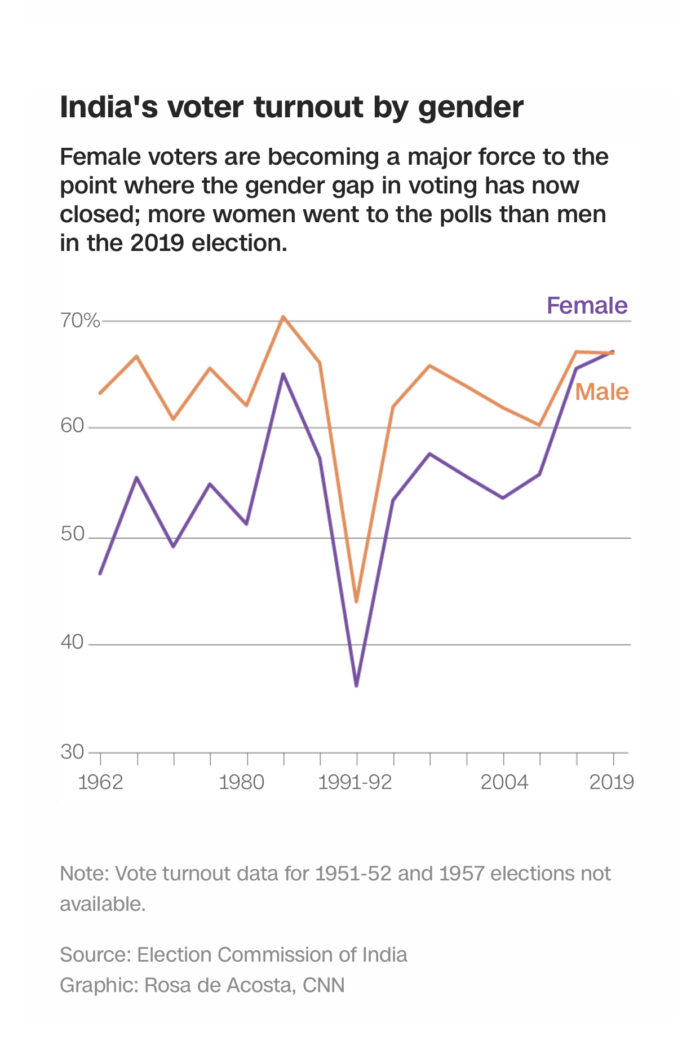

Turnout across all seven phases has slightly dipped from the record highs of 2019, yet India’s general election remains the largest exercise in democracy, with hundreds of millions showing up to determine who will lead the world’s most populous country.