(RNS) — Gathering with family and friends for the Passover Seder is the most Commonly celebrated of American Jewish rituals.

The ritual meal, celebrated tonight (April 22) at sundown with readings recounting the story of the Exodus, articulates who Jewish people are as former slaves and their struggle for liberation.

Yet this year’s Seder may be one of the most fraught and anxiety-producing in recent memory.

The source of the tension, the Oct. 7 Hamas attack and the ongoing war in Gaza, has triggered a broad reckoning over Israel and its war of retribution on Palestinians. It has fractured the U.S. Jewish community in painful ways, especially as younger generations increasingly side with the Palestinians over Israel.

In tried and true Jewish fashion, the Israel-Hamas war has produced a plethora of “Haggadah supplements,” pithy readings, poems and commentaries, to help guide the evening as people sit around the table and consider the themes of liberation and freedom.

They range in focus from those anchored in the trauma and pain of Israelis, 1,200 of whom were killed by Hamas on Oct. 7, to those rooted in the oppression of Palestinians, some 34,000 of whom have been killed in Israel’s devastating retaliation in Gaza.

“If a group is ideologically diverse, and diverse is probably too kind a word, if it’s a family that wants to kill each other, I think there are plenty of resources for multiple narratives, which I think is the key to the whole thing,” said Jay Michaelson, a rabbi and a journalist who spent years reviewing new Passover hagaddot published each year.For Pam Ehrenkranz, the CEO of the Jewish Federation of Greenwich, Connecticut, the central message of Passover this year is that some Jews are not yet free, namely the 100 or so Israeli hostages still remaining in Gaza.

A few months ago, Ehrenkranz, who was ordained a rabbi this month by the Academy for Jewish Religion, pleaded with the head of her seminary for help in planning her Seder.

“How do we go to the Seder saying we are free, when we know we are not free?” said Ehrenkranz, who has a daughter and two grandchildren living in Israel. “We know the threat to Israel’s existence is real, it’s imminent. How do we sit at a Seder and celebrate?”

Ora Horn Prouser, who heads the Academy of Jewish Religion, heard Ehrenkranz’s plea and joined forces with Rabbi Menachem Creditor to produce a 157-page supplement to the Haggadah, or manual, that focuses on solidarity with Israel.

“Seder Interrupted: A Post-October 7 Hagaddah Supplement” is intended to offer support and connection to people in pain.

It opens with the recitation of the order of the Seder and a commentary on the human need for order in the wake of trauma. There’s also a commentary on what it’s like to open the front door for Elijah the prophet, a ritual part of the Seder, at a time when many Israelis, especially those living in settlements alongside Gaza, barricaded themselves deep within their homes while Hamas militants stormed the doors.

“How dramatically different this seemingly normal experience — opening our doors — is from the hours and hours our people hid in safe rooms in the South of Israel, gripping the door handles and barring them shut with their bodies while Hamas rampaged inside their homes,” wrote Rabbi Beth Naditch, an educator and chaplain.

But many other Jews feel the Passover Seder cannot be complete if it only acknowledges the Jewish trauma of Oct. 7. They will be placing the emphasis on the oppression of the Palestinians.

“Yes, Jewish trauma is a part of this experience,” said Rabbi Brant Rosen, who leads Tzedek Chicago, an anti-Zionist congregation. “But also we need to recognize that that trauma is being weaponized at the current moment to unleash unspeakable violence that’s killed over 33,000 people, over half of them women and children, and that we’re on the verge of potential ethnic cleansing out of the south of Gaza.”

Rosen also compiled a set of Seder readings for his congregants who stand in solidarity with Palestinians. It’s called “Hearkening to the voice of Gaza”and includes several pieces of poetry and prose from people living in Gaza.

The supplement clearly spells out: “If we read the Passover story as a story of Jewish liberation alone or — God forbid — Jewish liberation at the expense of others, we will not have fulfilled the requirements of the Passover Seder.”

The congregation of about 350 families, many of them online from across the country and the world, will also host an in-person (and livestreamed) Seder at its Chicago headquarters on April 28.

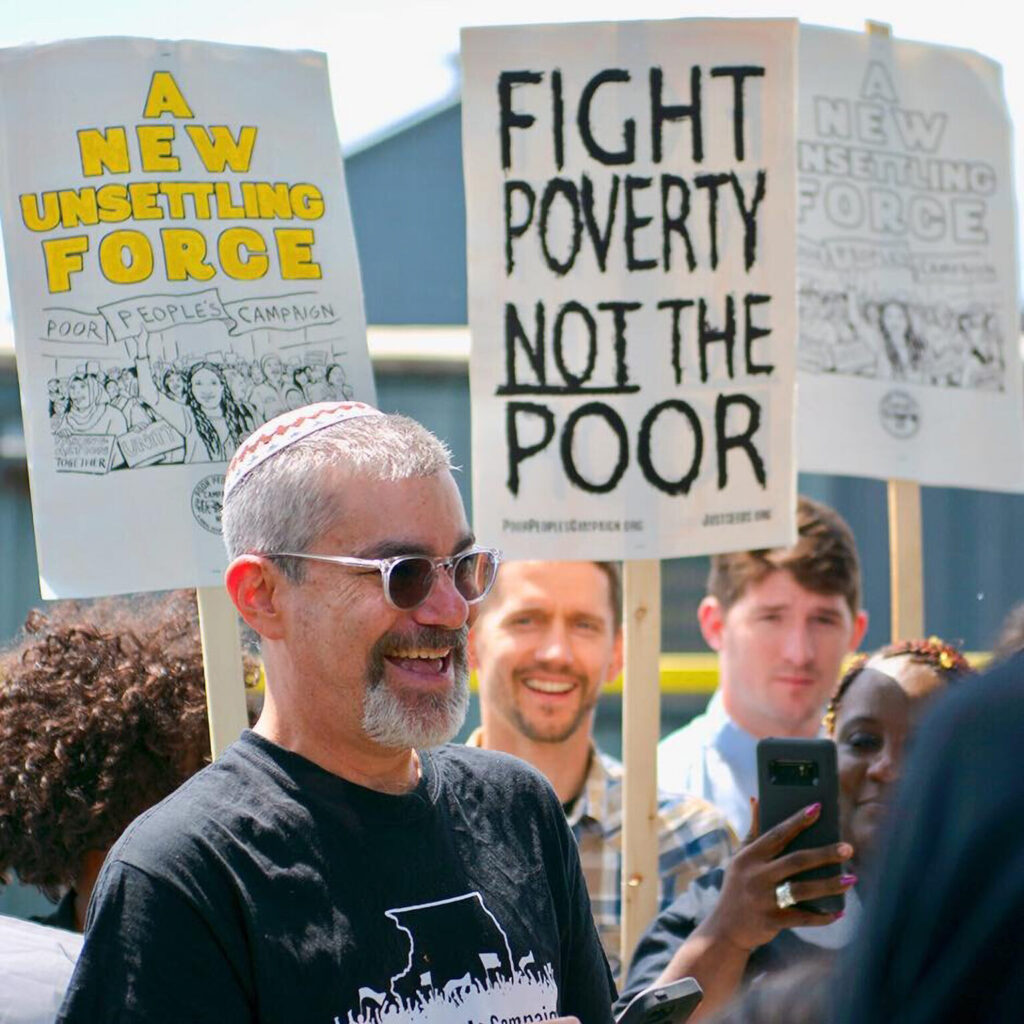

Using the Seder as an opportunity to talk about contemporary struggles for liberation may date back to Rabbi Arthur Waskow’s 1969 “Freedom Seder,” which used the civil rights movement and the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. as inspiration.

Nikki Morse, a member of Tzedek Chicago who lives in West Palm Beach, Florida, will be using parts of the congregation’s “Hearkening to the Voice of Gaza” as well as other selections curated over the years by Morse’s family members.

Morse’s online Seder for a dozen friends and allies, among them many members of the South Florida chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace, will include the Palestinian poet Taha Muhammad Ali’s “There Was No Farewell,”which Morse has used in past Seders.

The poem recounts the haste with which Palestinians fled or were driven from their homes during the 1948 Nakba, the mass exodus of at least 750,000 Arabs from Palestine. It echoes eerily with the haste with which the ancient Israelites fled Egypt, according to the traditional Haggadah text.

“Passover has always been my favorite holiday because I feel like it’s the essence of Judaism, the quest for justice,” said Morse, a professor of media studies at Florida Atlantic University. “I look forward to spending that time with people that I organize with for liberation and rededicating ourselves to that.”