Theo LeggettInternational Business Correspondent

BBC

BBCCritics call it “carspreading”. In the UK and across Europe, cars are steadily becoming longer, wider and heavier. Consumers clearly like them – a lot. They’re seen as practical, safe and stylish, and sales are growing steadily. So, why are some cities determined to clamp down on them – and are they right to do so?

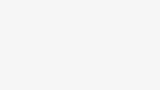

Paris is renowned for many things. Its monuments, such as the Eiffel Tower and Arc de Triomphe. Its broad, leafy avenues and boulevards, its museums and art galleries, its fine cuisine. And its truly appalling traffic.

Over the past 20 years, the city authorities have been trying to tackle the problem, by introducing low-traffic and low-emission zones, by promoting public transport and cycling – and most recently by clamping down on big cars.

In October 2024 on-street parking charges for visiting “heavy” vehicles were trebled following a public vote, taking them from €6 to €18 for a one-hour stay in the centre, and from €75 to €225 for six hours.

“The larger it is, the more it pollutes,” said the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, before the vote. The new restrictions, she claimed, would “accelerate the environmental transition, in which we are tackling air pollution”.

A few months later, the town hall claimed the number of very heavy cars parking on the city streets had fallen by two-thirds.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty ImagesCities elsewhere are taking note, including in the UK. Cardiff council has already decided to increase the cost of parking permits for cars weighing more than 2,400kg – the equivalent of roughly two Ford Fiestas.

The Labour-controlled authority said, “These heavier vehicles typically produce more emissions, cause greater wear and tear on roads, and critically pose a significantly higher risk in the event of a road traffic collision.”

To begin with, the higher charges will only apply to a small minority of vehicle models, but Cardiff plans to lower the weight threshold over time. Other local authorities are mulling similar steps.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesBut many owners say they are reliant on big cars.

Matt Mansell, a father of three based in Guildford, runs a technology company, as well as a property development business, and says he needs his Land Rover Defender 110 for ferrying around clients and children.

“I need to have enough space to put children in, with all of their kit – also, you can fit a door or a three-foot length of pipe in it,” he says.

“It’s very much a utility vehicle, but it’s presentable.”

‘Chelsea tractors’: Rise of the SUV

There is no question cars in the UK and Europe have been getting bigger over the years. Since 2018, the average width of new models on sale here has risen from 182cm to 187.5cm, according to data from Thatcham Research – an organisation that evaluates new cars on behalf of the insurance industry.

The average weight, meanwhile, has increased from 1,365kg to 1,592kg over the same period.

This is not just a recent phenomenon. Data compiled by the International Council for Clean Transportation shows the average width of cars on European markets grew by nearly 10cm between 2001 and 2020. Length increased by more than 19cm.

Some critics argue this is a worrying trend, because there simply isn’t enough room on Britain’s crowded, often narrow roads or in town centres.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe standard minimum width of an on-street parking space is 1.8m in many places. But figures published by T&E, a green transport campaign group, suggest that by the first half of 2023, more than half of the 100 top-selling cars in the UK were fractionally wider than this.

Then there is the rocketing popularity of Sports Utility Vehicles, or SUVs, cars that are at least loosely based on off-road vehicles, although in many cases the resemblance is cosmetic, and they lack genuine off-road features such as four-wheel drive.

The vast majority will never stray far from the tarmac, hence their rather derisory nickname: Chelsea tractors.

There are plenty of different designs out there, including utility models that you can actually use off road, swanky status symbols and legions of suburban family wagons.

What they all they have in common, however, is size. Even the smaller “crossover” versions, more closely related to conventional cars, tend to be taller and wider than traditional saloons, hatchbacks or estates.

Back in 2011, SUVs made up 13.2% of the market across 27 European countries, according to the automotive research company Dataforce GmbH. By 2025, their market share had grown to 59%.

Rachel Burgess, editor of Autocar magazine, believes it is their size that makes them so popular. “Everyone I’ve spoken to over the years who has bought an SUV says they like being higher up, they like better visibility, and they feel safer on motorways and bigger roads.

“It’s often better for people with kids to get them in and out of the car with that extra height; and also, for people who are less mobile, it’s much easier to get in and out of an SUV than a lower hatchback or saloon.”

Lucia Barbato, from West Sussex, says her second-hand Lexus RX450 SUV – a hybrid model – is vital for transporting her large family in an area with limited public transport. She runs a marketing agency from home and drives her three sons to the bus stop each day, so they can go to school.

“On a Monday morning with three boys, three school bags, three sports kits, and a trumpet thrown in the boot there isn’t even room in the car for the dog!”

Bigger cars, bigger profit margins?

The popularity of SUVs doesn’t just apply to mass-market carmakers. Porsche is famous for its sleek sports cars but the Cayenne SUV and the Macan crossover are its bestselling models.

Bentley’s Bentayga SUV accounted for 44% of its sales last year, while Lamborghini is increasingly reliant on its four-wheel drive Urus.

Put bluntly, consumers clearly love SUVs. Carmakers, meanwhile, are only too happy to meet that demand, because building bigger cars can be more profitable, argues David Leggett, editor of industry intelligence website Just Auto.

Getty Images and Bloomberg via Getty Images

Getty Images and Bloomberg via Getty Images“Profit margins are generally much higher on larger cars with higher price points. This is largely due to the laws of economics in manufacturing.”

There are, he points out, fundamental costs involved in building any car – for example operating a factory, design work, and the price of the main components.

But he explains that with small cars, these costs can make up a higher proportion of the selling price.

Daniele Ministeri, senior consultant at JATO dynamics, points out that many SUVs are closely related to conventional cars, and use the same basic structures.

“For some models, the main differences are limited to factors such as body style, suspension and seating position, allowing them to command an SUV premium price, without comparable cost increases”, he says.

The safety debate

Even conventional cars have been getting bigger in some cases. Take the current VW Golf hatchback, which is 9cm wider and 22cm longer than the version on sale in the mid-1980s. It is also several hundred kilograms heavier.

“If we look back to the early 2000s… safety programmes like Euro NCAP were just starting to deliver the safety message to consumers, smaller vehicles weren’t really able to absorb the energy of a crash very well at all,” says Alex Thompson, principal safety engineer at Thatcham Research.

“As safety measures have improved, a certain amount of weight had to be added on to vehicles to strengthen up safety compartments because they weren’t that strong back then.”

“Manufacturers have had to do things like improve structural crash protection, and fit more airbags,” agrees David Leggett.

“At the same time, they want to improve interior cabin space and put more features into vehicles, so the net result is rising pressure for bigger vehicle dimensions.”

Yet while bigger cars may be safer for their occupants, critics insist they are considerably less safe for other road users.

“Whether you’re in another car [or] a pedestrian, you’re more likely to be seriously injured if there’s a collision with one of these vehicles,” argues Tim Dexter, vehicles policy manager at T&E. He is also concerned about the implications for cyclists.

Research carried out in 2023 by Belgium’s Vias Institute, which aims to improve road safety, suggested that a 10cm increase in the height of a car bonnet could increase the risk of vulnerable road users being killed in a collision by 27%. T&E also highlights concerns that high bonnets can create blind spots.

Alex Thompson believes that taller, higher cars are more likely to harm pedestrians and cyclists, although he emphasises that vehicle design in recent years has “really prioritised” protecting vulnerable road users.

Some manufacturers have, for example, fitted external airbags to their vehicles.

In Pictures via Getty Images Images

In Pictures via Getty Images ImagesAs for the environmental impact, the International Energy Agency has said: “Despite advances in fuel efficiency and electrification, the trend toward heavier and less efficient vehicles such as SUVs, which emit roughly 20% more emissions than an average medium-sized car, has largely nullified the improvements in energy consumption and emissions achieved elsewhere in the world’s passenger car fleet in recent decades.”

The move towards electric vehicles should at least mitigate emissions from daily use significantly over time, although if the electricity they use is generated from fossil sources such as gas, bigger cars may well still pollute more per vehicle than smaller ones.

And other concerns about size and weight will still apply – in fact, with electric cars generally weighing considerably more than their petrol or diesel equivalents, certain problems could be magnified.

The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders says that 40% of SUVs are now zero-emission.

Its chief executive, Mike Hawes, has previously said that overall the carbon dioxide emissions of new SUVs have more than halved since 2000, “helping the segment lead the decarbonisation of UK road mobility”.

Penalties, taxes and the France model

But one option remains what has already been done across the Channel. France already imposes extra registration taxes on cars that weigh in at more than 1,600kg. Currently, this means a €10 (£9) penalty for every extra kilogramme. The penalty increases in bands, reaching €30 per kg above 2,100kg.

While it only applies to a relatively small proportion of current models – and electric vehicles are excluded – it can add up to €70,000 to the cost of buying a new car.

T&E argues that a similar levy should be introduced in the UK. According to Tim Dexter, “At the moment the UK is a tax haven for these large vehicles… We know the impact they are having on the road, on communities, potentially on individuals. It’s only fair they should be paying a bit more.”

David Leggett believes people could potentially be encouraged to buy smaller vehicles, particularly for use in cities. “There are opportunities to tweak tax regimes to make smaller cars relatively attractive,” he says.

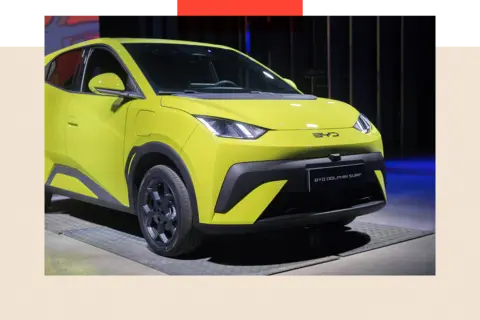

But ensuring there are enough runabouts to go around may be tricky. “There will always be a market for highly manoeuvrable and low-cost city cars in urban areas, but making them profitably is a huge challenge,” Mr Leggett says.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty ImagesHowever, several relatively low-priced small EVs have recently come on to the market, including BYD’s Dolphin Surf, Leapmotor International’s T03, Hyundai’s Inster and the new Renault 5. They will be joined before long by Kia’s EV2, and VW’s ID Polo.

For the moment though, SUVs remain firmly in charge.

“Clearly, people want SUVs, and I’m not sure what the answer to that is,” says Rachel Burgess. “But small cars are coming back, as the industry has understood how to make money from small cars in an electric world…

“I do believe everything is cyclical and trends come and go in every part of life, including cars. SUVs won’t be around forever.”

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.