(RNS) — One Sunday morning, a pastor steps up to his pulpit and — amid the swirling chaos of a country divided and mourning — preaches a eulogy for a felled leader and for our crumbling nation. The preacher turns prophet when he says, “The more we see of events, the less we come to believe in any fate or destiny except the destiny of character.” It is Sunday, April 23, 1865, and the sermon, delivered at Church of the Holy Trinity in Philadelphia by Phillips Brooks, is titled “The Life and Death of Abraham Lincoln.”

But what follows isn’t the story of the Civil War, the assassination of Abraham Lincoln or this sermon. It isn’t the story of how viciously polarized our nation was then or is today. This is the story of how all these events contributed to one of today’s most enduring and beloved Christmas carols, “O Little Town of Bethlehem.” It’s also the story of how one response to despair can be to make beauty from ashes, to sing the world toward greater faith and hope.

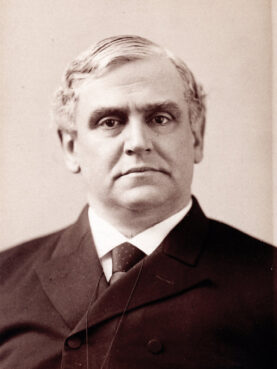

Brooks, author of “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” lived from 1835-1893. After graduating from Harvard University, he attended Virginia Theological Seminary and was ordained in the Episcopal Church in 1860. He became rector at Church of the Holy Trinity not long after, entering ministry just as the nation was plunging into civil war.

Brooks was outspoken against slavery and favored waging war against seceding states, views that divided not only the nation but even his own congregation. He was a towering figure, reportedly standing 6’4” tall. His sermons were as commanding as his stature, and he was considered to be one of the greatest preachers of his day. During the Civil War, he took on the role of chaplain at Gettysburg, traveling weekly by train from Philadelphia to Gettysburg and back. His sermons and lectures brought him and his church national attention, and his eulogy to Lincoln, preached in his home church, was widely read after being published.

The war, the sharp divisions inside and outside the church, the death of Lincoln and the death of one of Brooks’ brothers (from typhoid fever, contracted while serving in the Union army) left the mighty preacher exhausted and depleted. In “While Mortals Sleep,” published in June, Rachel Wenner Gardner relays how, mourning for his lost brother, the country’s lost president and the nation itself, Brooks began a yearlong sabbatical in 1865, setting off on a much-needed break for Europe and the Holy Land.

On Christmas Eve 1865, Brooks traveled on horseback from Jerusalem to Bethlehem. On that pilgrimage, he rode out to the field where it is said the shepherds saw the star and heard the angels heralding the birth of Jesus. Then he participated in a Christmas Eve service at the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.

Three years later, back home in Philadelphia, Brooks presented a little Christmas poem he had written for the Sunday school children about his Christmas in Bethlehem to the church organist and asked if the organist could set it to music.

That’s how “O Little Town of Bethlehem” was sung for the first time, on Dec. 27, 1868. Christians haven’t stopped singing it since, voicing each season an appeal to the “Child of Bethlehem” to “descend to us” once more.

It is striking that such a simple, soothing carol written for children (yet, full of rich theology and metaphor) could be born of such terrible loss. But it is not surprising. In a 1999 article in The Atlantic, poet Robert Pinsky, a former laureate of the United States, describes the connection between the peaceful Bethlehem Brooks encountered and the war-savaged home country he left for a while and returned to.

After the war ended, Pinsky wrote, “many little towns of the North and the South were unnaturally silent, because so many of the young men were gone. ‘The hopes and fears of all the years’ involve the Republic itself, and in that context the town’s ‘deep and dreamless sleep,’ beneath the silent stars, is the more unsettling precisely because it is dreamless, and therefore deathlike.”

One biographer wrote of Brooks’ Christian belief, “For Brooks, the final, non-negotiable bedrock doctrine was the Incarnation. God the Father sending his eternal Son, the Logos, to be born a man in first-century Palestine was the heart and soul of the Christian message; without the Incarnation, there really was no gospel to preach.”

There is, a century and a half after Brooks wrote this haunting carol, much once again (indeed, always) to lament, fear and grieve. Brooks — despite his position of power and influence (perhaps even because of it) — felt deeply the sources of these things in his own lifetime. He carried weighty burdens on his mighty shoulders, bore them across the sea, over hill, desert and dale, and back again. He emerged in the end faithful and hopeful. And he shared the source of that faith and hope to generations that followed and generations yet to come.

May we who feel great burdens — for our church, for our nation, for the world — do likewise.