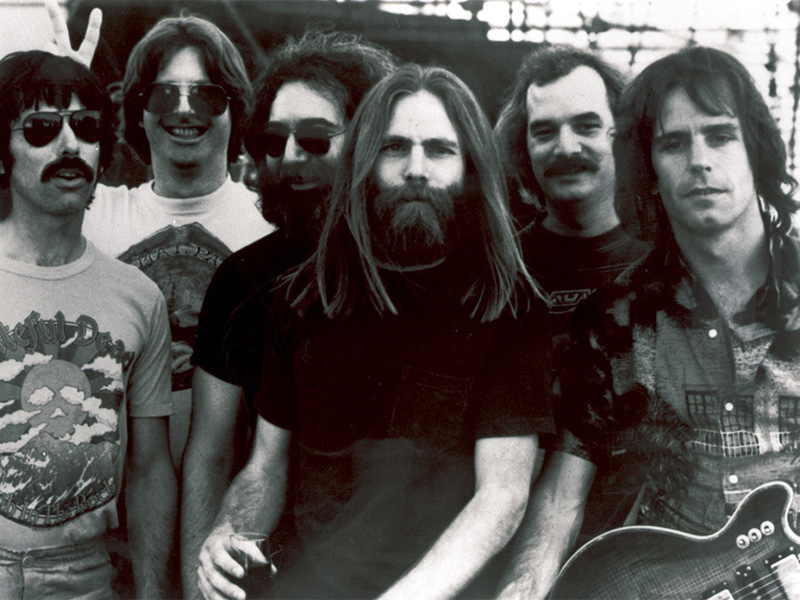

(RNS) — One of the largest “churches” in America has no building, but it has a liturgy, a sacred story, prophets and priests. Its congregation, while aging, still numbers in the hundreds of thousands.

Of course I am referring to the passionate devotees of the Grateful Dead, those whom we call Deadheads.

Deadheads worship the classic rock band — not in the crude sense of idolatry, but in the way religions actually function: through ritual, memory, shared language, pilgrimage and community.

The Deadhead culture began in the 1970s, as fans started traveling any distance, for any length of time, to attend the band’s concerts. The shows were unpredictable, unrepeatable and, to the faithful, transformative.

Their minhagim, or customs, were to record concerts, trade recordings with each other, annotate and publish set lists, and circulate lore. They created an informal economy revolving around tie-dyed shirts, veggie burritos, jewelry, buttons and stories. They even left their mark on American pop culture with an ice cream flavor named for Jerry Garcia, the late leader of the group.

The liturgy was the music itself. And the invisible liturgy was the sense of being part of a tribe, a roaming congregation bound not by geography but by shared experience. For many, the parking lot before the show was as holy as the show itself — a tent of meeting where strangers became kin.

This all returns to me now because we have reached the end of an era with the death of Bob Weir — the rhythm guitarist, singer, co-founder and the last visible steward of the Dead’s original spirit. With his passing, the Grateful Dead moves fully from living memory into sacred memory.

Weir was not Jewish, though a striking number of his fans are. Still, when I sift through the Dead’s music and mythology, I find Jewish resonances everywhere — echoes of values, questions and longings that sound uncannily familiar.

Consider one of the band’s most enduring songs, “Uncle John’s Band” (1970). The song is peppered with the names of old-time folk songs and allusions to Emily Dickinson. It starts:

Well, the first days are the hardest days, don’t you worry any more,

Cause when life looks like easy street, there is danger at your door.

Think this through with me, let me know your mind,

Wo, oh, what I want to know, is are you kind?

When you really get down to it, isn’t that a question we would want answered about anyone? “Are you kind?” Do you have enough chesed, or lovingkindness, within you?

When you strip religion down to its essentials, that is often the question that matters most. Different faiths have different stories, rituals and languages. But ultimately, we want to know: Does this religion produce human beings who are more compassionate, more aware of one another’s fragility?

Consider “Box of Rain” (1970).

What do you want me to do, to do for you to see you through …

What do you want me to do, to watch for you while you’re sleeping?

Well please don’t be surprised, when you find me dreaming, too.

Walk into splintered sunlight

Inch your way through dead dreams

to another land

Maybe you’re tired and broken

Your tongue is twisted

with words half spoken

and thoughts unclear

What do you want me to do

to do for you to see you through

A box of rain will ease the pain

and love will see you through.

The late lyricist of the Dead, Robert Hunter, had written the song for bassist Phil Lesh to sing to his dying father. It is unusual in a popular music culture that often avoids death or romanticizes it. And yet the song insists that love — not certainty, not theology, not even belief — is what carries us through. And at the end of life, when the props fall away, it is love that sees us through. That is not only a Dead lyric. It is a Jewish truth.

And then there is the song that has become, for many Deadheads, an actual hymn, “Ripple” (1970). (Check out this international version.) I once officiated at the funeral of a young man who died far too soon. He was a Deadhead, and his family asked me to include a Dead song in the service. There was no contest, when you hear the lyrics in full.

Anyone steeped in Jewish texts hears the echoes immediately: King David and his harp; overflowing cups from the Psalms; living waters not made by human hands.

What happens to Dead-ism now? Like any good religion, it has not died, but it has transformed. Tribute bands crisscross the country, performing the music with astonishing devotion and improvisational skill. There are Deadheads who collect recordings the way monks once copied manuscripts. They compare versions, argue over tempos and curate playlists like prayer books.

On my best days, I believe that when we reach out to each other, it is as if we are reaching out to God. God is the fountain of living waters — m’kor mayim chayim — that was not made by the hands of men. There is a repository of love. God is a place of rest for our aching, yearning, journeying selves.

A universal religious message — a longing to return to the Source, to holiness, to the best of ourselves, to the best of our history — is in the best of our texts, including those by the Dead. And, yes — if I knew the way, I would take you home.