(RNS) — Near the end of the Rev. David Black’s time on the stand in a federal courtroom in Chicago this month, the judge asked the Presbyterian Church (USA) minister how his faith was holding up.

Black was there to testify in an ongoing lawsuit against President Donald Trump’s administration regarding the use of force by federal immigration agents against protesters. That includes Black himself: he was shot in the head and body with pepper balls as he was praying outside an Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center in Broadview, Illinois, in September, according to a video captured that day.

According to Chicago journalist Dave Byrnes, Black responded to the judge by saying his experience in Broadview had only deepened his faith, adding, “This is the consequence of preaching the gospel to a government that is not unlike the Empire of Rome.”

It was the kind of radical spiritual defiance Black has come to be known for since he was thrust into the national spotlight for his activism outside the Broadview facility, where critics allege immigrants inside are being mistreated and where a growing number of fellow faith leaders have repeatedly protested the actions of ICE and Department of Homeland Security agents. Images of Black, who has been lauded by politicians and fellow activists, being shot with pepper balls and pepper-sprayed by police have come to represent faith-based opposition to Trump’s mass deportation agenda and earned renewed attention to liberal-leaning religious beliefs.

But in a pair of phone interviews with Religion News Service, Black, who has protested at Broadview numerous times, insisted his spiritual message isn’t new and that the focus should ultimately remain on immigrants, and not just aggressions against clergy. He also stressed that he is not alone, and that a wide network of faith leaders continues to show up at Broadview, despite the danger. He referenced the Rev. Hannah Kardon, a Chicago-area Methodist minister who was recently arrested while protesting outside the Broadview facility, and noted other clergy have also been struck with pepper balls while protesting there.

The Rev. Hannah Kardon, left, is pulled from a group of demonstrators by Illinois State Police outside the Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention facility in Broadview, Ill., Oct. 17, 2025. (Video screen grab)

Black, who “grew up in evangelical missionary churches all around the world” before becoming a Quaker in college and eventually being ordained as a Presbyterian minister, is quick to argue that while messages he preaches at Broadview are attracting attention today, they’re rooted in an old, widely known theology which he frames as “fundamentalist.”

“Fundamentalism is just talking about the basics of what Jesus says, what the Bible instructs us, and what our theology and doctrine calls us to do to believe,” he said. “When we are fundamentalists about those things, it really provokes us to be taking a very progressive stance in the world — or at least a stance that reads to the world as politically progressive — because it’s a stance that’s fundamentally nonjudgmental, fundamentally rooted in love, solidarity and interest in mutual aid and compassion.”

Black pointed to the church where he serves as senior pastor, the First Presbyterian Church of Chicago, as an example of this tradition, calling it a “church of troublemakers, misfits and mystics.” Believed by many to be the oldest congregation in the Chicago area, the church — often referred to as First Church — has also long been among the city’s most unapologetically progressive. It is said to have organized the region’s first abolitionist society and been active in the local temperance efforts — the latter out of concern that workers were being exploited by bosses who would “ply them full of alcohol and then gradually not pay them and only give them alcohol in return for their work,” Black said.

The church also helped organize Chicago-area portions of the Underground Railroad, housed the area’s first public school and was among the first — if not the first — to integrate its classrooms. First Church, Black said, also publicly declared it would disobey the Fugitive Slave Act and later denounced and actively worked against the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers. According to the church’s website, the congregation eventually hired an interpreter in the 1890s to translate services for the growing number of Chinese immigrants who had joined the church.

First Presbyterian Church of Chicago. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

First Church even made national headlines in the 1960s, when the congregation worked with a major local youth gang to help deescalate violence which, church leaders argued, was being exacerbated by the tactics of local police. Members of the gang turned over scores of weapons to the church, but tensions with police resulted in officers raiding First Church in 1967, sparking investigations by the U.S. Senate and the Presbytery of Chicago.

These days, First Church describes itself as a “progressive church with traditional theology.” Black says the congregation has seen lots of new faces after his activism made national news.

“We’ve had a lot of new visitors to our church, particularly people who will tell me they’ve never been to church before, or they haven’t been to church since they were little kids, or since they came out of the closet — or whatever the story may be,” Black said.

He added: “I’m seeing almost a revival of Christianity through what’s happening at Broadview in Chicago.”

The Rev. Quincy Worthington, another Presbyterian minister who has attended protests at Broadview with Black on multiple occasions, said he understood why Black’s encounters with DHS agents have attracted so much attention.

“I think it causes a shock to the conscience of good people, moral people, people who are deeply faithful, to see a man who is just doing his best to follow Jesus and call for mercy to be met with such excessive violence,” Worthington told RNS in a text message.

He added: “I can’t help but think what happened was the kingdom’s way of bringing into the light what the empire is trying to do in the darkness.”

It’s a theology that has caught the eye of politicians as well. In the weeks since clips and photos of his various violent encounters with DHS agents went viral, Black has appeared on national news networks such as CNN and MS NOW and been celebrated by Democratic lawmakers such as Rep. Pramila Jayapal of Washington and Rep. Becca Balint of Vermont.

Balint shared photos of Black last month on her Bluesky feed, the images overlaid with quotes of him discussing his activism at Broadview. The text was pulled from a recent “shadow hearing” focused on the government’s treatment of immigrants and activists in Chicago, which was hosted by Jayapal last month.

“Incredibly powerful words from Pastor David Black,” Balint’s post read.

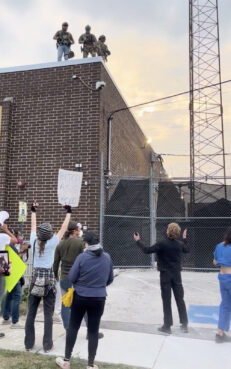

The Rev. David Black prays below masked agents on the rooftop of an Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention facility in Broadview, Ill. (Video screen grab)

At the same time, Black’s activism has been derided by DHS, which called him a “pastor,” using quotation marks, in an X post that referred to the footage of him being shot with pepper balls. A Newsmax anchor accused him of being “an Antifa member masquerading as a pastor.” And concerns about the treatment of Black and other clergy protesting at Broadview have been dismissed by Republicans such as House Speaker Mike Johnson, a Southern Baptist. Despite the speaker being asked repeatedly by RNS and other reporters about Black’s encounter with ICE agents, Johnson has insisted he hasn’t seen the widely shared footage, arguing instead that ICE agents haven’t “cross(ed) the line” and that religious freedom does not give faith leaders the “right to get in the face of an ICE officer and assault them.” (The footage of Black being shot in the head with pepper balls does not show him in the face of officers, who instead appeared to be firing down at him from the roof of a building.)

Black responded to Johnson by name at the “shadow hearing,” urging the speaker to “get the name of my Lord and savior Jesus Christ out of your mouth.” Asked about Johnson by RNS, Black accused the speaker of “weaponizing and equipping the forces of Rome that rounded up and executed Jesus.”

“My sincere hope for Mike Johnson is that he be called into his own repentance and clarity about his own faith,” he said.

But even as he spars with Republicans, Black and other religious leaders in Chicago have made clear their messages are drawn from their faith, not from either political party. Black and others have been critical of Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker, a Democrat, noting that it is Illinois state police who have arrested demonstrators outside Broadview in recent weeks — not ICE.

And in his appearance at the shadow hearing, which was organized by Democrats, Black made a direct appeal to leaders of the party.

“There is a new democratic movement in this nation. It is pluralistic and it is intergenerational, spiritually rooted and uncompromising in solidarity,” Black said. “It is time for the Democratic Party to decide if it will be the party of the people, the party of liberation and justice.”

Black has continued to demonstrate at Broadview, recently preaching a kind of sermon in front of police during a demonstration. And while Black himself is not at every protest, the numbers of faith leaders willing to demonstrate at the facility are only increasing: At least seven others were arrested at a single protest staged outside the building last week.

Illinois State Police and Cook County Sheriff Police detain an individual wearing a clerical collar outside an Immigration and Customs Enforcement processing facility in the Chicago suburb of Broadview, Ill., Nov. 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh)

Meanwhile, Black said his church is beginning work on a “deliverance ministry” — an effort he says is a response to Jesus’ call to “heal people and cast out demons.” He argued activists who have protested at the Broadview facility “are recognizing that there is a demonic presence” associated with the building and that the Christian tradition “has very direct and plain ways of dealing with it.”

“For us, it’s about people’s personal experiences of oppression and repression and suppression being cast out of them in very literal, embodied ways — but also the ways that we’re doing that on a systemic level,” he said.

The task before them, Black said, is how to cast “demons out of American politics, and out of the institutions that enable things like ICE and ICE’s operations.”