(RNS) — I might have to restart my stamp collection. I am going full geek.

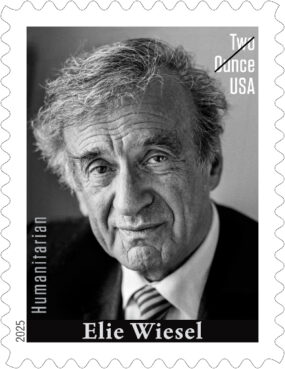

Why? Because the United States Postal Service released a stamp honoring Elie Wiesel, the Holocaust survivor, writer, teacher, activist and Nobel laureate. It is the first time in recent memory that a Jewish survivor and witness has been elevated in this way. His face now travels across the country, carrying a single word: humanitarian.

I am buying several books of those stamps, not because I send much mail these days, but because when I do, I want to see his face on those envelopes and to be reminded of what he demanded of us: vigilance, compassion and moral courage.

To honor Wiesel is not merely to remember what he suffered. It is to take up what he required of others — to see, to speak, to resist.

In his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech in 1986, he said: “We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.”

The Elie Wiesel stamp. (Image courtesy USPS)

Those words echo across time. Because once again, we live in an age of silencing and silence.

Across the world, voices that dare to speak for human dignity or for Jewish survival are shouted down. Jewish students on college campuses — some barely 18 years old — are intimidated, shouted at, harassed and sometimes physically threatened. They have been told that Zionists are not welcome, and when most American Jews identify with some form of Zionism, what those words really mean is that they don’t want Jews there.

Young people say that they are afraid to wear a Star of David or attend a Hillel program. They fear being photographed there, worried it could hurt their future careers. This is happening at academic institutions that once defined enlightenment and free thought.

And, on Yom Kippur, as Jews gathered in prayer in Manchester, England, a synagogue was attacked. Worshippers ran for safety on the holiest day of the Jewish year — in 2025, not 1938. Two people died and two others were injured.

If Wiesel were alive, I believe he would have no patience for euphemisms about such hatred. He would not allow moral fog to obscure moral fact. He would say what he always said: that antisemitism, like every form of bigotry, is a disease of the soul — and that indifference to it is its most dangerous carrier. He would remind us, as he did in his Nobel lecture, that the opposite of love is not hate, but indifference.

He would not be surprised that antisemitism has returned. He knew it never disappeared; it only slept. But he would be heartbroken that it now hides behind the language of justice, that people chant for human rights while denying the humanity of Jews.

For Wiesel, I think today’s Jewish students — isolated, mocked and vilified — would be the center of the universe, as would the frightened worshippers in Manchester. So would all people, anywhere, who are silenced for their faith, their conscience or their identity.

I often find myself asking WWWD? What would Wiesel do?

In 1985, when President Ronald Reagan planned to visit a cemetery in Bitburg, Germany, containing SS graves, Wiesel stood before him and said, “Mr. President, that place is not your place. Your place is with the victims of the SS.” It was one of the most extraordinary acts of moral clarity in modern times. He could have turned this into a tongue-lashing of the commander in chief, but instead achieved his purpose by lifting Reagan up, saying he was better than that.

That courage was born not of ideology but of conscience. Wiesel never confused politics with morality. He would remind us that democracy itself depends on moral decency.

And yet, Wiesel was not only an activist. He was also a teacher — a lifelong student of Jewish texts and ideas. He wrote not only about Auschwitz but also about biblical figures, the ancient sages and the Hasidic masters. For him, they were not remote ancestors but living interlocutors. For him, study was a conversation between the generations.

Here are just a few of my favorite snippets:

Of Moses he wrote: “Moses failed in everything but memory. He gave us memory.”

Of the biblical prophets: “What they did was unravel the significance of the present so as to understand its consequences for the future.”

Of Job: “Perhaps faith is precisely the refusal to stop asking.”

Of the ancient rabbis: “The real meaning of Talmud lies not in monologue but in dialogue. Not in solitary introspection but in confrontation. Hillel and Shammai, Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Yishmael, Rav and Shmuel, Abbaye and Rava: the law is decided according to the one or the other, but the decision-making process, the collective debate preceding the decision, is as important as the outcome. … The rabbis argued not to win but to understand. They believed truth was not a possession but a pursuit.” And, “To study is to listen to the conversation between generations.”

Of the founder of Hasidism, the Baal Shem Tov: “He taught that God is everywhere — even in exile, even in darkness. Especially there.”

Wiesel knew that study was itself a form of activism, and perhaps the richest form of spiritual resistance.

I imagine what Wiesel would say now, as we contemplate the Israel-Hamas peace plan that is unfolding before our eyes. I believe he would say he has seen too much blood to believe in easy peace, but too much suffering to stop believing in peace itself.

He would argue the return of the hostages must come first because no people can speak of peace while its sons and daughters are in chains. As for a Palestinian state — yes, perhaps, if it can be born not out of hatred, but out of responsibility.

Peace will not come from signatures on paper; it will come when both peoples can look into each other’s eyes and see not enemies, but human beings. Until then, hope must remain our rebellion against despair.

Each of the Elie Wiesel stamps is a tiny portrait of moral courage, whispering his eternal message to remember, learn, speak and hope. And, to never, ever be silent.