SOUTH BARRINGTON, Ill. (RNS) — In the summer of 1992, a reporter made a pilgrimage to the Chicago suburbs to get a firsthand look at Willow Creek Community Church, a congregation rumored to be the future of American religion.

What he found was worshippers swaying to a rock band, a humorous skit with a spiritual message, a sermon about how God could make their lives better — a service that bore more than a passing resemblance to an episode of “Saturday Night Live,” which debuted the night before Willow Creek opened in the fall of 1975.

The story in the Chicago Reader by Robert McClory, himself a former priest, ran under the headline “We have seen the future of religion. And it is slick” — and asked, “Is this religion for the 21st century, or just the latest in religious gimmickry? Perhaps it’s a little bit of both.”

In fact, nearly everything McClory saw would be completely unremarkable to many churchgoers today. Willow Creek, which turns 50 this week, became a new model of American religion, which replaced tall steepled churches, stained glass, hymns and robed clergy with pastors in jeans backed by chart-topping bands, video screens and smoke machines, a worship style that has been summed up as a Coldplay concert followed by a TED Talk.

At its peak, Willow Creek’s model drew more than 25,000 worshippers each weekend and armies of volunteers, who sought to love God and save the world. All of it was overseen by a former youth pastor named Bill Hybels, the son of a wholesale produce salesman, who had a knack for marketing and way with Scripture, and his army of followers.

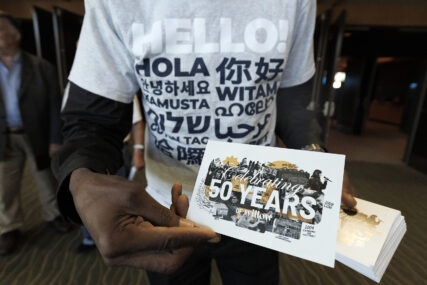

Greeters welcome congregants for a service at Willow Creek Community Church on Sept. 7, 2025, in South Barrington, Ill. (RNS photo/Carlos Javier Ortiz)

But just as familiar to today’s Christians was Willow Creek’s unraveling, with accusations of sexual misconduct in 2018 followed by denials, then a rash of resignations, and plummeting donations. Five years after the church celebrated its 40th anniversary in a packed-out United Center in Chicago, Willow Creek went into a COVID-19-aided financial and attendance tailspin that raised serious questions about its survival.

By then, Hybels was long gone, having resigned while still denying the accusations against him. A task force of evangelical leaders late concluded in 2019 that the accusations against him were credible.

The scandal and the COVID-19 pandemic left the church with years of struggle and an uncertain future.

On Saturday and Sunday (Oct. 11-12), the church will gather to celebrate 50 years of ministry, with a new pastor in place, attendance on the rebound after years of decline, and signs of hope for the years to come.

It’s been quite a journey from the church’s humble beginnings in a struggling suburban movie house.

In October 1975, at the Willow Creek Theater in Palatine, Illinois, a handful of volunteers, most of them barely out of high school, showed up early on a Sunday morning to sweep up popcorn and get the place ready for services.

Willow Creek Community Church worships together at the Willow Creek Theater in Palatine, Ill., in the 1970s. (Photo courtesy of Willow Creek Community Church)

Not long before, religion sociologists Don Miller and Wade Clark Roof had started to describe Americans as a generation of seekers — which made Willow’s seeker-friendly approach to ministry appealing.

“All of that just hit at the right time,” said Scott Thumma, director of the Hartford Institute for Religion Research and an expert on megachurches.

Nancy Beach, a former teaching pastor at Willow, has mixed emotions about the church’s early days. She was there at the beginning, having first met Hybels while a high school student at South Park Church in Park Ridge, Illinois, where Hybels started his ministry as a youth pastor.

Members of that youth group formed Willow’s core at its founding, selling tomato plants door to door to raise money for the startup church. At each door that opened to them, Hybels and other leaders would ask the house’s occupant if they went to church.

The Rev. Bill Hybels, senior pastor of Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington, Ill., speaks on Jan. 26, 2012. (Photo by Marc Gilgen/Creative Commons)

Beach missed the first service — held Oct. 12, 1975 — but arrived at the church soon after. She didn’t stay long. Those early days were difficult, with too many young leaders, too many new converts and little structure or accountability to keep people in line.

“We were just making it up as we went along,” Beach said in an interview.

“I sensed God saying, ‘Trust me, it doesn’t have to be what you think,” she said, “and I have a big adventure for you.’”

Willow Creek had continued to grow, building its own church on its new 90-acre campus in South Barrington, Illinois, northwest of Chicago in 1981.

The church got its big break when the Harvard Business Review began to pay attention to what the church was doing at the end of the decade. In 1989, management guru Peter Drucker mentioned the church, along with the Girl Scouts and Salvation Army, in an article about what businesses could learn from mission-driven nonprofits.

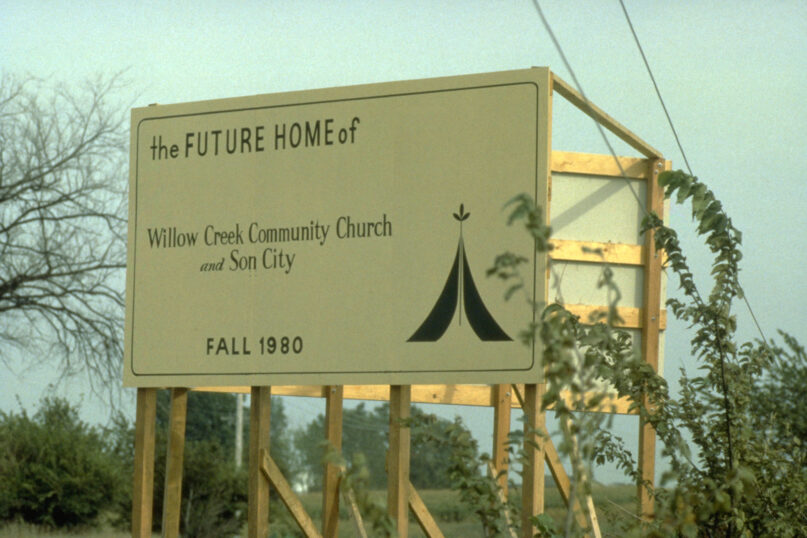

Signage for the future main campus of Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington, Ill., prior to 1980. (Photo courtesy of Willow Creek Community Church)

A few years later, Santiago “Jimmy” Mellado, then a grad student at Harvard’s business school, wrote a case study in the Harvard Business Review that gained national attention. The study told Willow’s origin story, how before founding the church, Hybels and other leaders had asked people what kept them away from church. They found that people were turned off by boring services, irrelevant sermons and churches asking for money with no proof that the money was doing any good.

“The pastor made people feel guilty and ignorant, and so they leave church feeling worse than when they entered the doors,” Mellado wrote, summarizing some of the claims of Willow’s founders. “They attributed their success to the simple concept of knowing your customer and meeting their needs.”

After writing his case study, Mellado worked for Willow Creek for two decades before becoming the CEO of Compassion International, an evangelical humanitarian group. In a recent interview, he said the seeker-friendly focus was only part of Willow’s success. The church gave new converts and established members alike a seven-step process that showed them how to grow their faith and make a difference in the world through active ministry. A key part of that process was the Wednesday night “New Community” service, designed to help members grow in their faith.

Willow stretched “both sides of the spiritual spectrum,” Mellado said. “There was this value, all people matter to God, therefore they ought to matter to us.”

That value — and the way the church focused on helping people grow in their faith — can get lost amid Willow’s decline. Neither the seeker-friendly outreach of the church or its other ministries could have happened without a core group of believers who were devoted to sharing their faith with others — and who put their time and money to work for that cause.

For years, Mellado ran what was known as the Willow Creek Association, a network of churches that shared Willow’s methods. He said the work was not for the sake of insiders like him, but to put people to work making the world a better place for others. He said that at its best, Willow wanted to be a good church, doing God’s work.

“Let’s just be the church that God’s calling us to be,” he said. “And I think all the rest of the stuff will take care of itself.”

The story of Willow Creek’s rise must be told against the background of nondenominational Christianity’s phenomenal growth in the United States over the past half-century. In 1975, established Christian denominations — the United Methodist Church, the Roman Catholic Church, Presbyterian Church, the Southern Baptist Convention and others — ruled the religious landscape. Today, denominations are running on fumes, said Ryan Burge, professor of practice at Washington University in St. Louis who studies the changing religious landscape; nondenominational churches rule the day.

But other nondenominational megachurches were not Willow Creek. Its association ran an annual Global Leadership Summit where not only preachers but Fortune 500 executives and politicians, including President Bill Clinton, spoke and joined discussions about how to empower organizations and people. The church always seemed to be pointed toward the future, not engaged in arguments based on past practices.

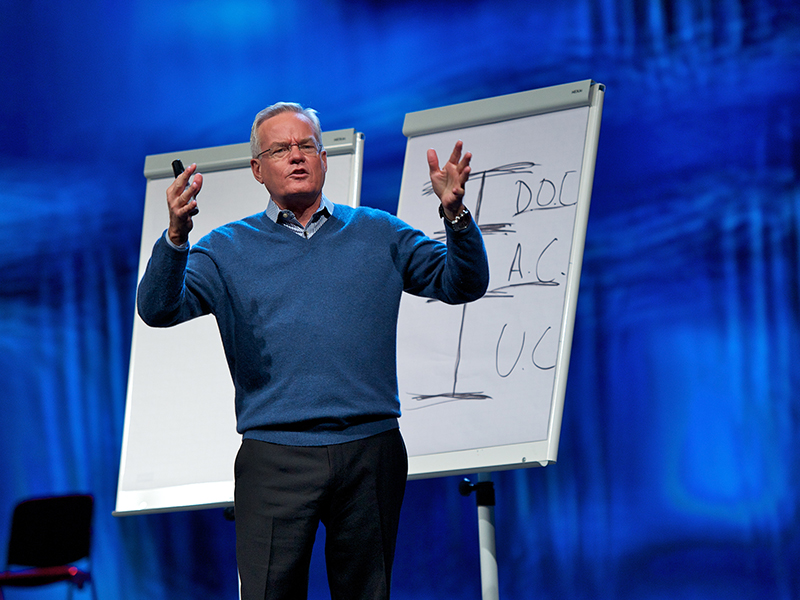

The Global Leadership Summit, on the main campus of Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington, Ill., on Aug. 9, 2018. (Photo courtesy of Global Leadership Summit)

While conservative Christian in its theology, Willow was pragmatic about its evangelism, down to who ran its small groups.

“In actual experience, it was easier to find high school girls who were spiritually mature and skilled in leadership than it was to find guys,” Hybels once wrote, in describing why the church had women in leadership.

“From a practical standpoint, it would have been unthinkable not to allow girls to lead.”

Beach recalled that as a college kid, she was leading adult women in Bible studies. “The women I tried to serve were mostly old enough to be my mom,” she told RNS.

In 2004, when Willow was drawing 17,000 worshippers on Sundays, the church built a 7,400-seat auditorium for $65 million. The new building nearly doubled the previous capacity. A decade later, its format had become an irresistible ideal.

“Any community that is able to draw in 24,000 worshippers in a single weekend is clearly doing something right,” said a writer for America, the Jesuit magazine, explaining why his erstwhile Catholic brother had defected to Willow.

But by 2015, when Willow was celebrating its 40th anniversary, hard times were already on their way.

Pastor Bill Hybels speaks at American University in Washington, July 1, 2010. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak)

After several years working behind the scenes trying to get Willow Creek’s elders to address allegations of misconduct by Hybels, a group of former church leaders, including some of Hybels’ close friends, went public in March 2018.

According to those former leaders, Hybels had a history of alleged inappropriate behavior toward women at the church, including inviting women to his hotel room and giving unwanted physical affection.

Hybels, who did not respond to a request for an interview, denied any wrongdoing. Eventually more women, including his former assistant, accused him of sexual misconduct.

On April 10, 2018, Hybels, who had been planning to retire, resigned from Willow Creek. While he denied most of the allegations against him, he said he had made mistakes.

“I realize now that in certain settings and circumstances in the past I communicated things that were perceived in ways I did not intend, at times making people feel uncomfortable,” he told church members, according to Christianity Today. “I was blind to this dynamic for far too long. For that I’m very sorry.”

Elders at Willow Creek Community Church lead a service of worship and reflection on July 23, 2019, in the Lakeside Auditorium on the church’s main campus in South Barrington, Ill. (RNS photo/Emily McFarlan Miller)

Eventually almost every top leader at Willow Creek would step down, including Hybels’ handpicked successors and the entire elder board.

“We are sorry that we allowed Bill to operate without the kind of accountability that he should have had,” elder Missy Rasmussen told the church in announcing the resignations. “Our desire going forward is to retain what is good and pure about Willow, but to drive out the dark places that are unhealthy.”

Scandal was not the only factor haunting Willow. Times had changed since Willow built its massive sanctuary. While stadium-sized churches were cutting-edge in the first decade of the 2000s, they were falling out of fashion. Today, newer megachurches hold multiple services in smaller satellite campuses that are cheaper and more effective. Willow now has five satellites but has trouble filling its big room in South Barrington, except for special events or when it rents it out for concerts.

In mid-May of this year, Shawn Williams, who’d been named senior pastor of Willow six weeks earlier, led a meeting in his office to talk about the future, about six months ahead of the church’s 50th anniversary.

For the first time in years, the church had good news. Attendance was back up to nearly 10,000 per weekend, and the budget was back in the black. The turnaround was credited to David Dummitt, who had just ended five years as pastor.

Pastor Shawn Williams preaches at Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington, Ill., on Sept. 7, 2025. (RNS photo/Carlos Javier Ortiz)

Senior staffers sat on couches and comfy chairs in jeans and other casual wear, chatting about the Chicago Cubs, who had been doing well and were up 8-3 that afternoon.

“You never know with the Cubs,” warned Matt Sundstedt, Willow’s executive pastor of operations. “A good April doesn’t mean anything.”

Williams, who joined Willow in 2020, said that for the past few years the church has focused on getting healthy and strengthening its core values. Now, he said, it’s time to start dreaming. “We’re going to put vision back in front of us,” he said. “We’re going to chase some things — and if God were to honor that, we can grow.”

Williams cited new baptisms, the church’s growing diversity and the Willow Care Center, which includes a grocery store, a car repair ministry, dental and legal clinics and other services, serving thousands of the church’s neighbors each year. The staff was looking forward to anniversary services on Oct. 11-12 at the South Barrington campus.

Willow’s leaders realize there is a tension in the church’s story. Great things happened in the church’s past, and important ministry still happens today. Yet Hybels’ misconduct and the church’s failings in dealing with his fall still haunt the church. Many church members who left have never returned, while critics say the church still hasn’t done enough for the women who accused Hybels of misconduct.

Hybels has rejected a formal attempt from Willow to reconcile.

The Willow Care Center in South Barrington, Ill., offers a variety of resources to thousands of people each year. (Photo courtesy of Willow Creek Community Church)

Katie Franzen, the church executive pastor of ministries, said the church does not want to bury the past, but learn from its mistakes and continue to move in a better direction. The church’s 50th anniversary, she said, is a chance to tell the church’s whole story and “to really celebrate the pieces of our history that highlight God’s beauty and his faithfulness and his ability to use broken people.”

“But also, to say, here are the mistakes and the brokenness that we had a chance to really learn from and to turn a new page,” she said.

Williams said he was asked, after being named senior pastor, if he wanted Willow to regain its former prominence, when the church saw itself as one of the best ministries in the world. He said the church has different goals these days. “Our goal is not to become the most influential church in America or to make a cover of a magazine,” he said. “That’s not our goal. Our goal is to be our best for the world.”

He was mindful of those across Chicago’s metro area — Chicagoland, in TV newsspeak — who are far from God and need the kind of community Willow can offer. And many of their neighbors have day-to-day needs — like trying to put food on the table —that the church can help with. There’s still a lot of work to do.

“We want to be a church that helps reach unchurched people, or de-churched people or disconnected people. How you go about it is different today than it was in 1975, but the heartbeat hasn’t changed,” he said.

Dan Egan, a Willow Creek member since high school, said he is hopeful for the future. Now 38 and a new dad who plays in a Willow worship band, he attends the church’s Huntley campus, about 25 minutes from the main location. Egan said he trusts the new leadership, in particular the leaders at Huntley. And that matters.

“I wouldn’t stay with Willow just to stay with Willow,” he said. “But I will stay with Willow if they continue to do good things.”

He has stayed, he said, for his friendships, and because of the church’s extensive outreach programs, including a prison ministry he has volunteered with. “That’s not tame, we’re-going-through-the-motions church stuff,” he said.

But those who remember Willow’s full arc are more tentative. Beach, who was one of the women alleging misconduct by Hybels, said, “I do think God used the church in a remarkable way, and I got to be a part of that, but then this just deep sadness that leadership failed us in other ways.”

These days, she also prays for the current leaders of Willow Creek, saying she is hopeful for the church’s future

“I’m not saying it has to be huge again, or it has to be a trailblazer,” she said. “I just want it to be a healthy biblical community for the people that it can reach there.”

Dave Burrage, 62, first visited Willow Creek in the early 1980s while a student at the University of Wisconsin. After graduation, Burrage moved to the area and began attending Willow. Before long, he’d joined one of the groups for young singles and become a small-group Bible study leader. “That’s how I got very plugged in at Willow — through serving,” he said.

Over the decades, he said, Willow Creek’s mission has stayed the same. “Back in the day, it might have been a desire to see people become fully mature in Christ,” he said. “Now, we talk about being rooted in Christ.”

Burrage said that in recent years, he’s been encouraged by growth in diversity at the church. “If you attend Willow at this point on a given Sunday, you will see a tremendous amount of diversity,” he said. “That’s been a really healthy thing.”

Burrage believes Willow has been humbled by the failings of Hybels and all that followed. Some of his friends found it too painful to be at the church, but Burrage stayed because he had ties that went beyond the leaders and because he believed in the mission and ministry.

The longtime church member remains saddened that Hybels has disappeared. “It’s a really stark reminder that not all stories end well,” he said.

Few expect Willow to recapture its past glory, an assessment Thumma agreed with. That’s in part because Willow’s size and approach to ministry are no longer unique.

Pastor Shawn Williams preaches at Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington, Ill., on Sept. 7, 2025. (RNS photo/Carlos Javier Ortiz)

In the early 1990s, an attendance of 10,000 would make a church one of the largest in the country. Today, more than 90 churches average more than 10,000 attenders; at least 30 churches pull in more than 15,000. The largest church in the country, Life.Church, based in Edmond, Oklahoma, claims to draw 85,000 to its more than 40 locations, according to Outreach Magazine’s list of the largest churches in the country.

Thumma said America has also changed in the 50 years since Willow was founded. Most of the people Willow attracted in the early decades had at least some experience of Christianity. “It wasn’t like they were completely ignorant of what it meant to go to church or to be a Christian,” he said.

Today, a growing number of people have none of that residual knowledge or experience of Christianity, especially younger Americans. According to Pew Research, 44% of Americans aged 18-25 have no religious affiliation.

But the megachurches that have surpassed Willow Creek have done so by perfecting what Hybels and Willow Creek started in 1975. A good many other megachurch pastors have followed Hybels into ignominy, having broken the trust of people who got them there.

The main campus of Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington, Ill. (Photo courtesy of Willow Creek Community Church)

Others have thrived. And former leaders at Willow have gone on to start new churches, head major Christian nonprofits or other ministries, continuing on the church’s vision of building up the faithful and sending them out in the world to do good.

Not all stories end well. But the young people who invested their lives in the church 50 years ago — and those who continue to believe in the mission — hope that the story of Willow Creek will endure.

“I would love Willow to be a place where people constantly find hope,” said Williams, in looking to the church’s future. “And hope can come in a lot of different ways. It might be hope for my marriage, it might be hope for me as a parent, it might be hope for my next meal. It might be eternal, spiritual hope. Hope comes in a lot of ways, but our heart dies when we don’t have hope.”